重温基本

The Basics Revisited

张利/ZHANG Li

从整体名声上说,我们的时代不是个对基本事物感兴趣的时代。随着量子物理学与混沌理论蔓延到我们日常生活的点点滴滴一一或者至少被智者们声称是这样一一似乎任何与绝对或基本有关的事物都变得过时了。正如基阿尼·瓦蒂莫所说,在后现代,一切都只是一种阐释而非结论,包括这个论点自身。

建筑学也发生了变化。宽泛的语义学联想总是试图上建筑学远离物质空间的纯粹喜悦;而且无论这些联想多么牵强,总在事实上被认为是学术新领域的定义。设计实践本身越来越接近文艺批评而不再是空间干预。

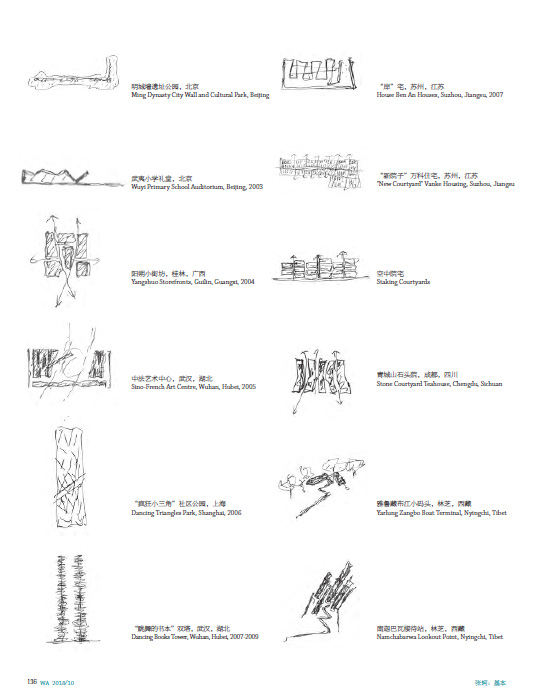

然而,还是有些人试图拒绝这种潮流的一一张轲便是其中之一,他选择重新审视基本。在过去的20年中,他和他的同事长期致力于基于句法学的设计实践探索。无论是在密集的中国城市还是在广袤的中国乡村,他们的空间实验一直在延续。

张轲自主、中立的取向赋予了他的作品以一种颇具识别性的语言。对材料和空间的抽象、不涉及伦理(或接近不涉及伦理)的操作使他的作品对任何评述而言都是开放的。它们有时在中国和西方会得到截然不同的解释,这恰恰证明了这种抽象性和中立性。正是建筑学的基本,而不是别的任何任何东西,让张轲的作品成就其本身。在张轲的作品中能够看到几何:理性的、但令人愉快的多边形几何。它既不同于正统现代主义者的多米诺原型,又无视死硬派参数化主义者的炫技翘曲。那些相信欧几里德几何必然会导致无聊的人可能需要重新考虑一下自己的主张了,因为张轲的几何游戏确实取得了一定的有机复杂性,很容易让人联想到像沃尔特·弗德尔那样的非正统现代先锋试验。

在张轲的作品中能够看到光:充足,甚至过度的日光从四面八方渲染着通常十分狭促的室内空间,呈现出令人印象深刻的氛围。正是在由建筑的开口(窗户、隧道、光井,随便你怎么称呼它)带来的光晕下,张轲把他最大胆的冒险应用到材料与身体空间的互动之中。

在张轲的作品中能够看到材料:对巨石意象的痴迷使张轲致力于对不同的材料进行各种各样的实验,以试图模仿混凝土的三维塑性。其结果有时精彩绝伦,有时毁誉参半,但无论如何,从未枯燥乏味。

在张轲的作品中能够看到功能:或更准确地说,类似于功能的目的性。张轲的建筑通常突出泛化、柔性、粗犷但具有社会性企图的功能。它们从来不是其建筑的目的,而是支持其建筑逻辑的方法。在张轲的建筑中,有时我们很难找到具体的业主或最终使用者。但是,必须说明的是,既然功能中立性可以有助于让建筑保持更明确的设计自主性聚焦,那么何乐而不为呢?

最后,在张轲的建筑中能够看到乐观:对设计干预的乐观。与一些西方评论完全相反的是,对于过去的30年中国发生的超高速城市化,张轲的回应既不是抵抗也不是叛逆。他可以选择适应,但拒绝折衷纯粹的、由设计产生的价值。他试图在所有类型的建筑中找到合适的切人点,从那开始通过设计导致正向的改变。也许有人会说,张轲的设计乐观主义既是一种结果又是一种对他设计作品所处环境的适应性机制:很明显,在中国,最大的挑战与最大的兴奋长期共存。

我们在为一期专辑中浏览张轲的作品,希望通过它们重温建筑的基本。当然,对任何的基本而言,重温永远好于忘却。

Our time is not known for its interest for the basics. With quantum physics and chaos theory flexing their muscles in our daily life, or at least said to be so, anything with hints to the absolute or the essential seems outdated. As Vattimo puts it, in the post-modern age, everything is just an interpretation rather than a conclusion, even this argument itself.

There has been shifts in Architecture as well. Broad semantic associations pulling architecture away from the pure joy of physicality of space, no matter how far-fetched, have become the de -facto definitions of new scopes that are widely celebrated. The practice of design itself is becoming more of critique than of intervention.

There are though, a few people trying to resist the trend. ZHANG Ke for one, chooses to revisit the basics. Over the past two decades, he and his colleagues have been committed to syntactical design enquiries and have been taking continuous experiments, both in the dense of super-high-rise Chinese cities and in the thin of the vast Chinese countryside.

The autonomous, neutral approach of ZHANG Ke has imparted his works with an identifiable language. The abstract, ethics -free (or quasi· ethics -free) treatments of material and space are open to all kinds of commentaries. The fact that ZHANG Ke's works are sometimes interpreted dramatically differently in China and in the west is a proof of this abstraction and neutrality. It is exactly the basics of architecture, more than anything else, that make ZHANG Ke's work what they are.

There is geometry. Rational, yet delightful polygonal geometry that defies both the Domino of the orthodox modernists and the warping of the die-hard parametricists. Those who believe Euclidean geometry is only destined for boredom may have a second thought. ZHANG Ke has certainly achieved some organic complexity in his play of geometry, reminiscent of some non-orthodox modern pioneers those of Walter Foerderer.

There is light. Ample, even excessive daylight from all directions renders the usually humble interior spaces with an impressive aura. It is by the openings (windows, tunnels, wells, you name it) of light that ZHANG Ke take his boldest adventures into materiality and body space.

There is material. An obsession with monolithic quality drives ZHANG Ke to a variety of experiments, trying to mimic the 3D plasticity of concrete in all kinds of materials. The results are sometimes sound, sometimes arguable, but never boring.

There is the programme, sort of. General, flexible, broad- brush-definition yet social programmes are usually used to support ZHANG Ke's buildings. They are not the ends of the buildings, but the means. Sometimes it is even hard to find specific owners or users of certain buildings. After all, being programme-neutral helps to maintain more autonomous design focuses, so why not?

Finally, there is optimism: the optimism of design interventions. Quite contrary to some western observations, ZHANG Ke is neither resistant nor rebellious in his reaction to the super-fast urbanisation taking place in China in the past 30 years. What he cannot compromise, however, is the value generated purely by design. He tries to find the anchor point in all typologies from where he can deliver a positive change through design. One may argue that the design optimism of ZHANG Ke is both a product of and an adaptive mechanism to the environment his practice is in: the challenging and exciting situations in China.

Do let ZHANG Ke's works in this special issue take us to some basics of architecture. When it comes to the basics, it's always better to revisit than forget.

张轲

张轲生于1970 年,于2001 年成立标准营造事务所。在过去的17 年里,标准营造有大量建成作品,已经成为新一代中国建筑师中,关键且最具创新精神的角色之一。近年来,标准营造的设计作品包括瑞士诺华制药上海园区办公楼、北京胡同更新系列项目及西藏系列项目等。

张轲及标准营造,近年来多次在欧洲举办主题个展——如2018 年法国巴黎路易·卡雷住宅建筑个展、2017 年德国比勒·菲尔德建筑个展、2017年芬兰赫尔辛基建筑博物馆个展、2015 年德国柏林凯达环球建筑个展、2015 年奥地利多恩比恩奥德堡建筑个展等。2016 年张轲受邀参加第十五届威尼斯建筑双年展主题展。

2018 年,张轲“微胡同”的实体模型被纽约现代艺术博物馆永久收藏,成为博物馆中代表当代中国建筑实践的第一个作品。其作品还曾参加在维也纳应用艺术博物馆(MAK)、法兰克福建筑博物馆(DAM)、伦敦维多利亚和阿尔伯特博物馆(V&A)等地的诸多展览。他的论著已被众多建筑媒体报道出版,包括Casabella, a+u, Domus, MARK, Detail, Bauwelt, Garten+Landschaft, Topos, Icon, Architectural Record 以及Harvard Design Magazine 等。

张轲曾受邀在纽约建筑联盟、柏林当代艺术中心、布伦瑞克工业大学、智利天主教大学及维罗纳博物馆等授课讲学。还曾在鹿特丹建筑论坛2.0、米兰设计周、赫尔辛基设计周、悉尼设计周、博洛尼亚CERSAIE 及纽伦堡Architektur-Fenster-Fassade 论坛等活动中担任主讲人。

张轲是2017 年阿尔瓦·阿尔托奖、2016 年阿卡汗建筑奖的获得者。此外,他还荣获2011 年维罗纳国际石造建筑奖、2010 年建筑实录国际十大设计先锋、2008 年中国建筑传媒奖青年建筑师奖、2010 及2006 年WA 中国建筑奖优胜奖等。

1998 年,张轲获哈佛大学设计学院建筑学硕士学位,并先后获清华大学建筑学学士及建筑学硕士学位。2016 年起在哈佛大学设计学院任教。

2016- 至今 哈佛大学设计研究生院客座教授

2001- 至今 标准营造 ZAO/standardarchiteture创始人、主持建筑师

1996-1998 哈佛大学设计学院建筑学硕士

1993-1996 清华大学建筑学院建筑学硕士

1988-1993 清华大学建筑学院建筑学学士

获奖

2017 阿尔瓦·阿尔托奖

2016 阿卡汗建筑奖

2013 中国博物馆建筑大奖优胜奖

2012 芝加哥国际好设计奖(“明”托盘,Alessi)

2012 智族GQ 年度设计师

2011 国际石造建筑奖

2010 美国建筑实录国际十大设计先锋

2010 车尔尼科夫建筑奖国际十位优秀建筑师特别提名

2010 WA 中国建筑奖优胜奖

2008 第一届中国建筑传媒奖,青年建筑师奖

2006 WA 中国建筑奖优胜奖

Born in 1970, Zhang Ke founded ZAO/standardarchitecture “标准营造” in 2001. With a wide range of realized works over the past 17 years, the studio has emerged as one of the most critical and innovative protagonists among the new generation of Chinese architects. Recent works include the Novartis Campus Building in Shanghai, a number of Hutong transformation projects in the historic centre of Beijing, and various buildings embedded in the landscape of Tibet.

The work of Zhang Ke and his studio has been the subject of several solo exhibitions in Europe- most recently at the Maison Louis Carre in Paris, France, 2018; the Bielefeld Kunstverein in Germany, 2017; the Museum of Finnish Architecture in Helsinki, Finland, 2017; the Aedes Architekturforum in Berlin, Germany, 2015; and the Zumtobel Lichtforum in Dornbirn, Austria, 2015. In 2016, Zhang Ke was invited to exhibit in the Central Exhibition at the 15th Venice Architecture Biennale.

In 2018, a concrete model of Zhang Ke’s work Micro-Hutong was acquired into New York MoMA’s permanent collection, becoming the first project representing contemporary Chinese architecture at MoMA. Zhang Ke’s work has also been featured in exhibitions at the MAK in Vienna, the DAM in Frankfurt, the V&A in London, and published in architecture magazines including Casabella, a+u, Domus, MARK, Detail, Bauwelt, Garten+Landschaft, Topos, Icon, Architectural Record, and the Harvard Design Magazine, amongst others.

Zhang Ke has lectured at the Architecture League of New York, the KW Institute for Contemporary Art in Berlin, Technische Universität Braunschweig, Universidad Católica de Chile, and the Castelvecchio Museum in Verona. He was a key speaker at the Architecture 2.0 Symposium in Rotterdam, Milan Design Week, Helsinki Design Week, Sydney Design Week, the CERSAIE in Bologna, and the Forum Architektur-Fenster-Fassade in Nuremberg.

Zhang Ke was awarded the Alvar Aalto Medal in 2017, and the Aga Khan Award for Architecture in 2016. Other notable awards include the International Award Architecture in Stone, Verona, Italy 2011; the Design Vanguard by Architecture Record, 2010; China Architecture Media Award (CAMA), Best Young Architect Prize, 2008; and the WA Chinese Architecture Award, Winning Prize, 2010 and 2006.

Zhang Ke received his Master of Architecture from the Harvard Graduate School of Design in 1998 and his Master and Bachelor of Architecture from Tsinghua University in Beijing. He has been teaching Option Studios at Harvard GSD since 2016.

Zhang Ke,

2016 - present Visiting Professor, Harvard University, Graduate School of Design

2001- present, Founding Principal, ZAO/standardarchitecture

1998, Master of Architecture M-Arch II, Harvard University, Graduate School of Design

1996, Master of Architecture, Tsinghua University, School of Architecture

1993, Bachelor of Architecture, Tsinghua University, School of Architecture

Awards:

2017 Alvar Aalto Medal

2016 Aga Khan Award for Architecture

2013 China Museum Architecture Award, Winning Prize

2012 Good Design Award (Ming Tray for Alessi)

2012 GQ designer of the year

2011 International Award Architecture in Stone, Verona Italy, Winner

2010 Design Vanguard of the World (Architecture Record)

2010 Chernikov Prize, Special Mention (top ten young architects in the world)

2010 WA Chinese Architecture Award, Winning Prize

2008 China Architecture Media Award (CAMA), Best Young Architect Prize

2006 WA Chinese Architecture Award, Winning Prize

张轲访谈

Interview with ZHANG Ke

张利/ZHANG Li

张利:上大学之前怎么决定要学建筑的?

张轲:我高中的时候想学物理,特别喜欢物理。我哥哥和他的大学同学打赌看谁的弟弟或妹妹能考上清华建筑系,回来他就忽悠我说学建筑多酷,可以背着画夹,在学校里特酷,我说我不学,我还是要学物理。我们小时候都看过南斯拉夫的电影《桥》,建筑师参加抵抗运动,反法西斯,去炸自己设计的桥,结果跟自己的桥同归于尽了。我说这一辈子的成就,说不定和自己同归于尽了,不永恒。所以我当时特别不愿意,我还是要学物理。后来,我哥带我去新华书店,去看建筑书,那时候书少,估计看到的是KPF、SOM这类商业事务所的作品集,我记得当时看到的照片,一堆建筑师,背后是克莱斯勒大厦(Chrysler Building)或者洛克菲勒中心(Rockefeller Centre)那种大厦的大尺度模型,觉得这个挺酷的,就被他成功忽悠了。就这样,高考半年前,我跟学校说我要考清华建筑系,大家都觉得我疯了。我一个普通中学的,就算学习好,考上的可能性也很低。我哥是重点中学,我那个学校只出一些体育尖子,排不上前几名。当年我放弃了学物理,有点误入歧途的意思。后来我在清华教课,经常问学生为什么学建筑?大多数回答都差不多,基本上是觉得建筑跟物理、数学有点关系,但又和艺术有点关系。主要因为不懂、不知道建筑是学什么的。到了寒假,我去新华书店查了一堆建筑书,还挺有动力的。但直到入学的时候,我都没学过画,在清华一直待了8年。

张利:对,你后来跟着胡绍学先生读研。

张轲:在清华我觉得咱们那时候特别好,8年,5+3,本科5年,硕士3年,我感觉时间更松快一点。

张利:现在多是4+2的。

张轲:差两年差好远,当然本科其实差不多,但是本科也多一年,读研也多一年,就不一样了。在清华我印象比较深的是,我们的美术课到大二结束,正式停了。我们有一个美术小组,董功在其中,华黎有时候也参加,我们从大三就开始了,经常周末出去,在清华北门外小村子里画画,把清华传统的色彩写生稍微突破了一下。这个活动一直持续到了上研究生都没停,前前后后画了8年,这点和一般的建筑师不太一样。

张利:上纲上线的话,你从小或者是你血液里包含的对空间形式的好奇心和渴望突破禁锢的基因,其实是在清华的时候通过美术小组得到了延续,是吧?没被杀死。

张轲:肯定没有,清华这一点我觉得挺好的,不管你是什么流派、组织,全球其他学院是有摇摆的。但清华对于建筑、艺术比较执著,我在咱们这一拨同学里,感受得到这种执着的态度,非常明确,同时有比较强烈的竞争心理。当时学术交流方面,对外面的信息、国际上怎么回事还不太了解,但是这种执著给我的印象很深。

其次,清华的基本功训练还是挺厉害的,刚才说到我有8 年时间,比较松快,上学的时候有比较充裕的用于反思的时间,不是紧赶慢赶,一个题目(program) 一完马上就离校。研究生第一年有些课,第二、三年思考的时间还是挺多的,这样挺好。清华当时的建筑教育,一二年级水墨渲染、构成、“螺丝转”(用鸭嘴笔练习画螺旋线),其实鲍扎美术学院(Beaux-Arts)的传统很强,好像还夹杂一些莫斯科大学的训练传统,我觉得对于建筑院校是有教育意义的。现在想起来是挺正统的,没有太多可置疑的东西,技巧训练特别好,感觉很健康,就是1950-1960 年代传下来的教学传统都还在。

出国去哈佛大学设计研究生院(Harvard GSD,简称“GSD”),对我来说,当然从思想上有一个非常大的改变。最关键的改变一方面是知道了别人都在干嘛,全世界在讨论什么,视野不一样了,原来我们在国内再执著、再把建筑当作信仰,可能那个信仰其实只是商业的东西,到了GSD 才知道大家在做什么,知道全世界有什么不同的地方,知道自己在做的事情和历史是什么关系,和当代是什么关系,和别人是什么关系,这很重要。我产生了一种自我意识,意识到自己和当代有什么关系。

当然另一个方面对我自己来说,肯定是有启蒙,历史上发生启蒙运动的那个点,可能在个人身上发生了——开始知道设计的过程应该是非常严密的思考过程,而且设计项目的讨论过程可以是非常严谨的,是一环扣一环的,推导(reasoning)变成特别明确的一件事。但当时也有问题,20 多年前的GSD,当时包豪斯的遗风(legacy)其实还有,还挺强的,体现在设计师工作室课程(studio)里面,尤其是核心工作室(core studio),比如说拒绝渲染图(rendering),原来在清华学的那套完全不能用。对于我个人来说是特好的事,因为不能用渲染那些技巧,就必须用线来表达图纸,最多用些一个调子的灰,就是抽象画了,尤其是平面图。咱们上学的时候,不光清华,全中国尤其是美院,更严重,视觉表达都特别强,但是说到平面就瞎了,推不下去,但是包豪斯的建筑教育就非常严谨克制,还得把空间表达清楚,平面磨到一定程度。最终,平面图是可以阅读的,不需要看图面的视觉表达,远远地什么也看不出来,几张大硫酸纸、铅笔图,上面都是线,不用介绍,大家就去读。牛逼的教授读了3 分钟以后,说“I like it”,然后就开始讲。他先读你的平面,像读一本小说,读出一个空间的序列,事件(events)、发生发展(happening),其中空间的收放,不是简单的感觉的事情,是超越感觉的。

于是,我开始从清华的教育反思,一点鲍扎、莫斯科大学的基础技法再去写实表现,再加上一点儿赖特——清华当时咱们知道比较推崇的现代建筑师也就是赖特了。直到现在我认为清华在建筑教育上还是有问题的,现代主义的根好像并没有在清华扎得很深,我这么说可能稍微有点片面。有可能因为创办清华建筑系的那批人——梁先生和林先生——他们也去哈佛读了一年,但时间比格罗皮乌斯早了一年,没赶上现代主义在哈佛生根发芽,当时哈佛还是一个景观系。后来贝聿铭先生比他们晚几年到哈佛就学就幸运地赶上了,出现了完全不一样的思维方式。但是GSD 也有问题,我前段时间还写了一篇文章说,GSD 在某种程度上相当于包豪斯在美国的一个“转世”(reincarnation),因为格罗皮乌斯到美国以后,他创办了建筑系,做建筑系系主任。但是,后来从GSD 毕业以后,我花了很多年,需要摆脱(unlearned)哈佛的传统,毕竟有些太艰难(steep)了。

我记得可能10 年前保罗·鲁道夫、爱德华·伯恩斯(Edward L. Barnes)、贝聿铭,他们那时候都是一班的,回GSD 办了一个展览挺有意思的,叫Beyond the Harvard Box(2006),就是超越传统的包豪斯盒子。说明老一代建筑师也有同样的想法,因为被现代主义建筑洗脑的感觉是很强的,完全沉浸在其中。我在那两年——其实一年半就毕业,但我在那待了两年——感觉脑子里就是建筑历史书里那些经典的房子,想的就是那几十栋房子,毕业以后好多年要摆脱那些影响,然后开始放松(relax)。我觉得也是挺有意思的一个过程,学过以后再从中脱离开(unlearned),也是一个学习的过程,可能是回归到自我个性的小过程。

张利: 我跟其他几个人也都聊过, 旁观者也都有类似的看法, 对于你刚才提的这个“unlearned”,或者说你不是特别有一种教条(doctrines),你更不是任何的一种原教旨主义者(fundamentalist),好像是帮助你成功的重要因素,从你的职业生涯来看,你从来不像某些人,做建筑做到最后很累,细到里头,一点儿一点儿抠,好像总保持着一种相对放松的心态,你不在乎你已经获得的东西,或者说你已经取得的成功,已经放下了。我觉得这是很了不起的。包括你一开始我印象最深的就是咱们同学毕业多少年聚会的时候,你那会还开着餐馆,说:“我才不在乎甲方,甲方找我我才不急,甲方急。”那时候,其他人都想办法怎么去说服甲方,怎么把自己的想法说出来,你说:“我才不在乎,他爱改不改。”

张轲:这也对,上次有个朋友说,实际上我每个房子其实也挺累的,只不过最终的结果大家看不出来累。比如说我们现在的工作室,中间结构露多少不露多少,结构的形式到底是怎么露,过程中在落实每个细节的时候,都会有好几个选项(option),每个选项都要讨论(debate),分析多少次以后最后说那就是这个了,但是这个最后的结果不能让人觉得累,结果是轻松的。就像你写了一篇看上去很轻松的文章,但实际你省略的过程可能是很累的,这个累就是把累的东西都给去掉了。这个严格的系统下,怎么把这种系统刻意地去掉。所谓人性就是自我的这种直觉(in t u i t i on)能够保持到最后。如果说建筑一开始就是一个纯理性的东西,出发点就是理性的,我非常不认同彼得·埃森曼这套做法。我一直认为,建筑设计开始可能是非常感性的东西,当你确定以后,你要把感性(sensibility)或者直觉(i n t u i t i v e)的想法落实到一座建筑里,有极其多的技术问题,但是每个过程需要推导(reasoning),有非常严格的逻辑性,最后能把最初的看上去很轻松的感性(sensibility)变得可能更为加强的感受,落实下来。要有一定的轻松的状态,只是这种状态有可能是表面看上去的。

张利:那你认为哪怕是做到这个表面的轻松状态,而很多人做不到,包括很多很好的建筑师。在建筑上,你认为是本身的性格还是后天的东西在发生作用,比如,你有一套特殊的方法?为什么你能别人不能。

张轲:我真的没觉得别人不能,其实只要每个人真诚(si n c e r e),谁都可以。确实这中间是有一套方法的,这就是为什么教育很重要。但是中国的教育和国外的教育都有模式,如果简单地“被模式”了,不能走出来再找到自己的特性——每个人自己的特性——那就很难有突破。我一直反思自己做的事,感觉在整个过程中,无论在清华、GSD受教,都是不断的教育让自己被一定地模式化了,跳出教育体系再找到自己本身骨子里更喜爱的一个方向,再被模式化,再跳出来找自己,可能过程中间还要找,我倒觉得这件事是重要的大事。我还记得鲍勃·迪伦有一张照片特别酷。很多年前,他三五十岁的时候,拿一个牌子在纽约街头,上面写着“SUCKCESS”,不是“SUCCESS”(成功)。这种态度挺好的。而中国整体都有问题,大家都想着一定要怎么样。仔细想想,勒·柯布西耶到死之前,他写文章都认为自己有很多失败,虽然他给他母亲写的信里不断地强调自己已经很成功了,需要让他母亲去认可他。我觉得,最终还是因为你特别喜爱这个事,享受做每一个作品能够实现的那种快乐,比其他的东西都重要,我真这么想。

其他的可能从客观上对事业会有帮助,但是咱们作为建筑师追求的是什么呢?受到的认可度大了以后,自由度就更大了,但是咱们拿自由来干嘛呢?自由度更大不就是可以更好创作吗?可以更好地把自己梦想的东西实现,因为别人需要花更多的时间去说服别人。我觉得这个态度还是挺重要的,如果太在意(成功)的时候可能反而给人的感觉就是你说的那个,就是会累。

我记得有一个讨论特别好,建筑是“representation”,还是建筑“represent itself”。如果我们做的建筑能把所有其他的东西都去掉,它会有更强的自主性(autonomic)。虽然有点老生常谈,就是我现在碰见学生,我也会跟他们说,我说建筑师真的不是一个挣钱的行业,因为学建筑的都特聪明,大多数都很有天赋(talent),用这个天赋如果是想去挣钱,那全世界有好多个行业,赚钱效率比建筑要高很多,要想出名我觉得也有很多行业比这个更容易。

张利:说一个让你自己感到做得自由的建筑。

张轲:骨子里感到自由的……其实西藏那一系列的房子里前几个这种感觉最强烈。最早的是雅鲁藏布江最小的那个小码头和游客接待中心,那一系列因为欧阳,合作方的负责人,他是北大中文系的,他在西藏待了10年,我和他一认识就一起走徒步,基本上他不管,完全让我们来,从选址到内部功能到底要多大都由我们来定。他只是说要一个码头,没有任务书。但是在上海张江的诺华,它的限制是瑞士式的,面积半平米都不能多,半平米也不能少,比例要求、平面效果都把控得很严格。

张利:参与的建筑师有刘家琨、张永和,袁烽是不是也做了一部分?

张轲:袁烽做的是地下室内。

张利:还有隈研吾。

张轲:对,然后我是跟阿拉维纳(Alejandro Aravena)一起比他们晚一年开始的,但是我们要同时跟他们一起干完,所以我们被折磨的时间短一点,这变成了优势,后来发现他们前面那一批房子都被折磨、被压抑了。瑞士公司的设计过程,跟西藏完全是反着的,先拿到很厚的任务书(brief),细到要什么功能、每个功能几点几平方米,特别严格。建筑外轮廓线、高度都是确定的,规划是张永和做的。内部其实是自由的,是从内到外的一个过程,最后给的自由度其实特别大。对于建筑设计,瑞士甲方公司内部的决定层级非常高,他们对建筑师的态度,是我们作为签名建筑师,要承担的是向最后的指导委员会(steering committee)进行汇报并得到认可的责任,委员会通过了,剩下来一切都是由建筑师来控制。从你要选什么材料、用什么照明公司到景观设计的咨询公司(consultant),全都会支持你的决定,得到的支持度很大,而且要做几次1:1的打样(mock-up),花了几千万,楼梯、扶手、灯都制作打样,只要建筑师说好就确定方案,把打样拆了,现场重搭。楼梯在现场了搭一个1:1的,最后说可以,然后把这个楼梯拆了,重做一遍。

所以,我觉得可能在建筑设计的系统里,有两种自由。一种是西藏的那种自由,他给我足够的信任,我的责任也更大,要负担各种决策的责任,包括成本、实施、时间节点等等,什么都得管,但是他不会随便改设计。瑞士诺华的例子,要符合他们所有的要求,只要他的打样高层委员会决定了,他也不改你的设计,但整个过程各种咨询公司会告诉你这个不行、那个不行,各种斗争,在过程中间要特别坚持自己想要的东西。

比如幕墙,最后他们聘请了帮弗兰克·盖里做幕墙做了20 年的特里·贝尔(Terry Bell),正式的咨询公司是法国的RFR,给贝聿铭做过玻璃金字塔的咨询公司。但是他们大概是因为公司运营的时间长了,变得特别强调安全。特里·贝尔挺厉害的,施工图非常牛逼,这么厚的手画草图,研究幕墙窗棱的结点怎么扣到一起,他们拿去做最后的计算,因为它这个窗棱和玻璃是一体化的玻璃组件(unitized glass),等于半个窗框是在这个玻璃上,然后要做一个标准的开槽卡到一起。我的设计5m的层高,幕墙可见的宽度只是4cm,怎么做出来,最终幕墙结构还行,玻璃中间是开缝的。这种自由度,我负的责任就是说对建筑效果和空间和效率负责,其他造价那些东西都有人帮我算。当然我们说的这些都是技术上的,我很难说哪个对我来说最终更自由。

张利:两个批评性的观点,请你来回应一下,一是有人说你是机会主义者。你会更快把握一个项目或者是一个作品中你最适合的边界,然后尽量把它的效果最大化。

张轲:机会主义者,就是建筑都是关于机会的,每一个建筑都是关于机会的,但它是不是上升到机会主义,这个肯定就"overstated"(夸张)。建筑师对待每个场地都会看到它的机会,每个项目都有它的机会,实际上我们在做的就是对于这个机会的把握,发现问题。我一直在说建筑,全世界每年盖上百万千万的建筑,咱们做的有什么意义?我们难道就是作为甲方的工具吗?肯定不是,我们肯定还是要提出问题,这就在于每个项目我们看到了什么问题,我们置疑的是什么?我们创造了什么?我们的东西对别人有什么启发?所以从这个角度看,如果从功利的角度说,如果一个人想的是功利,为什么他老是抓住机会,但是我觉得只有不去做一个机会主义者,最后才能老是有机会,所有的机会都是背后玩命玩出来的。真正的机会主义者生活是有多苦?整天得计划设想,多没有意义。从长远来说,最后还是看作品的力量。

张利:第二个批评意见,有的人会认为你的建筑对工艺(craft)——特别是地方工艺(local craft) 、源自文化根源的工艺—— 没有特有意地去解释, 或者说, 你是更接近于一个世界主义者(cosmopolitan)或者国际主义者(internationalist)的。

张轲:"Internationalist"这个词,它已经有了历史风格化的东西。当年的"internationalist"是关于某几种风格、具体的做法的,所以我应该不是那种,但是这种看法有道理,我从来没有对地方工艺有过特别深的研究。

张利:换句话说,没有研究就不去刻意表现,并不是一个弱点,而你也喜欢那些表现或者是研究当地工艺的人。

张轲:是的,但是我确实不是专门干这个的。

张利:你不认为研究地方工艺是高人一等,或者说,你不认为对那些负有责任。

张轲:我不是反对那种做法,但我确实没有花太多的功夫在地方做法上,比如说我对当地的建造方式有兴趣,可能用了它的系统,但是我想更多的是做他们之前没做过的东西,比如说用木构怎么让石头飞起来,比如说我跟赵扬一起做的娘欧的小房子,木头梁是木构,但它绝对不是传统做法,传统的木梁上面不能承受这么多石头。我们的设计里,中间斜的飞起来的侧面的石头,在木梁侧面架个大角钢,用角钢托着这么厚的石头墙,那肯定不是传统的工艺。

我到目前为止没有研究地方工艺,但不代表将来不会研究一下。既然有人问了,说不一定哪天我仔细地研究研究。我们的一些材料实验,都是实验性的,并不是真正传统的技艺。这个批评是很中肯的,之前我没有想过。

张利:这是我听到非常好的回答。

张轲:这么一问还真的提醒了我,并不是说一个建筑师一定要研究传统的工艺对吧?但我觉得可能将来会研究。

张利:下面最后一个问题就比较带有挑衅的意味(provocative)。

张轲:问题都是比较挑衅的。

张利:因为你刚才也提到未来,我们就不问那些你是不是还考虑得普利茨克奖这种问题了,这种是商业媒体的,公众媒体的,你回答这种问题来说实在太简单了。想问的是这样的,其实在西方我也听到了这样的讨论,在他们评论家、批评家、历史学家的耳朵里,我们是拒绝简单用某些数字或者是我们讲到自然的那些标志——比如说你是哪年出生的——去划分人的属性,但好像历史学家总免不了掉入这个圈套。

张轲:你说代际(generation)?

张利:对,中国的两个代际,比如说你所代表1970年代以后的“翻篇儿的一代”("the generation that turning the pages"),在你之前已经有一些受到国际关注的建筑师了,你们之间有比较大的区别。你承认吗?

张轲:肯定是有区别的,但是年代划分这个,比如说柳亦春比我大几个月,我们头两天在里昂一起聊天,华黎也在,我不觉得我们是不同代的,但历史学家他总要专断地(arbitrary)去划分,否则他就没法说了。但是你说的这个早的代际,其实好多代了,就是前面这一代他们前面还有一代,比如说张永和跟他父亲肯定不是一代的。

张利:咱们说的所谓就是中国在“改革开放”以后,也就是意味着这一代出生时间不一定,但是受教育基本上是文化革命以后。

张轲:这一代和前一代是有很大区别的。

张利:而且你在翻篇也好,或者是什么也好。

张轲:我肯定不承认我是翻篇的那一个,我不知道这是哪一代,因为10年前我就说过,我是新一代,但是我表达的更多是一种立场和态度,当然不同岁数的人他的立场可能跟时代、跟他受教育的年代有关系,比咱们大一二十岁的人,他想的问题跟咱们想的问题一样,这个可能性其实很小。咱们这一代跟国际的这一代的横向界限可能更模糊。日本老一代,像丹下健三那一代——当然在丹下健三之前还有一代——中国应该跟日本不一样,因为到目前来说还不一样,将来也许过50年后可能很像,我不知道。当时他们很清楚就是把现代主义建筑融入日本,所谓日本性,跟日本传统结合,形式上的结合很强。将这个过程当作使命。可能老一代的建筑师、比我们大一代的建筑师,或多或少有这种使命感。我觉得也挺重要的,在他之后几代,现在就不需要再有这种所谓使命感或者责任感(responsibility),到伊东丰雄、妹岛和世、藤本壮介、石上纯也他们就不需要了。

新一代对于老一代来说,可能我们最开始年轻的时候是反叛的。那个时候我们刚回国,看来看去就他们几个,可能现在的年轻人,比如说比咱们年轻十几年的建筑师,刚毕业,可能也会觉得怎么老是他们几个人,会说我们也是这样子的。我们可能从革命变成了反革命,我们要时刻提防自己变成反革命。老一代建筑师肯定也奠定了我们获得更大自由的基础,这是肯定的。他们走过的路,带给我们的自由是我们可能不需要再走这一步了。最早梁思成那一代把中国的东西直接拿出来,让大家能够看到中国有中国的系统,终于有一代人探讨怎么把中国的形式当代化,但是这个阶段肯定是过去了。

我们的作品肯定跟中国有关系,但这个关系是跟当代中国的关系,当代中国是一个不断变化的概念。所谓“中国性”这个概念,本来是非常飘忽不定的,而且范围极广,我觉得任何人只要把它衍生(generalise)成一种东西,肯定都是很危险的,但是这种感受(sensibility),反而是非形象、非形式化的东西。建筑里很容易抓住这种感觉,我记得赫尔佐格曾经说过,他们上学的时候跟阿尔多·罗西学习,讲的是记忆,讲记忆是有符号的,同时又有很强的精神性。像赫尔佐格他们这一代我记得他们说的挺关键的话,就是如何做到能够吸收阿尔多·罗西的那个劲,同时又拒绝阿尔多·罗西,刻意地去回避那些具体的任何符号化的东西。仔细想想,他确实是这么做的,他不说我不知道,他其实对于罗西那一代是有继承的,但是继承不是说他做什么我就做什么,他可能拒绝前一代人做的东西,这也是一种经过思考的继承。如何区别这一代和上一代?每代人肯定是要想的,比我们再晚一代的人,他们如何区别他们跟我们?如果他没想清楚,他一定做不出更新的东西来,确实这个问题很provocative。

作者单位:清华大学建筑学院/《世界建筑》

访谈日期:2018-09-23

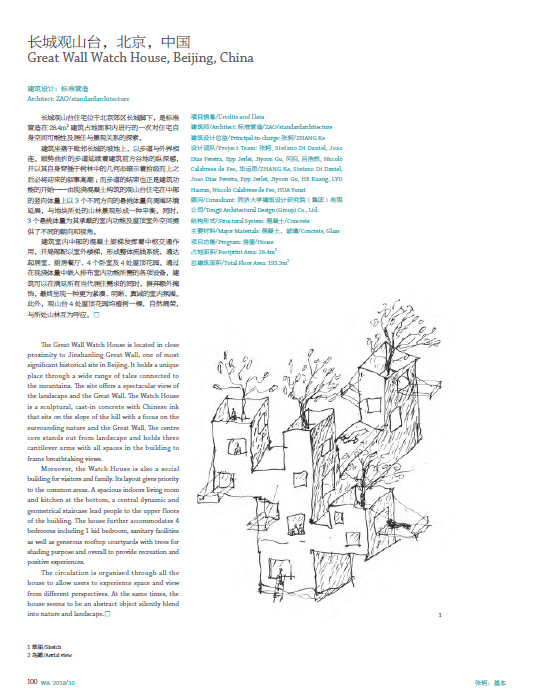

建筑叙事的真实性基础:张轲的作品

An Authentic Basis for a Narrative in the Name of Architecture: The Work of ZHANG Ke

爱德华·科格尔/Eduard Kögel

尚晋 译/Translated by SHANG Jin

今天,历史建筑的文化仍在塑造着中国的流行民族特征。无论哪个手册或宣传材料都有大屋顶或宝塔。近年来又出现了另一种叙事:千篇一律的摩天楼城市为大屋顶和丰富的历史形式提供了背景,却毫无地方特色。人们的城市失去了从生活环境中建立认同的简单观念。不仅是功能单一的城市住区,还有审美贫瘠的概念,都使建立认同的过程和对住区的责任感复杂化。但会被大众接受和关心的当代环境应是怎样的?

大型文化建筑的形式和公共维护义务或许有一种象征效果,但在小尺度的日常文化上才能看到建筑干预的真正意义。建筑师如何理解他们的工作,为发现的文脉赋予怎样的意义,这些问题与同使用者的紧密对话都是至关重要的。因为构成认同的建筑不会出现在绘图板上,而需要一群倡导者和守护者去抵御各种材料衰落的日常迹象。

今天的世界在很大程度上是以表面形象为特征的。在这样的世界中,建筑也因一种耀眼的外衣闪闪发光——它不会老化,而会破碎。这无疑是难以将建筑理解为一种人们用情感纽带来支撑的文化的原因之一。因为没有材料就只剩下形式,而那也可以是非常武断的。号称先锋的建筑可能最终很快被丢到历史的垃圾堆中,而它的象征力在建成时就已经枯竭。

因此,对于建筑师的问题仍是如何在特定的情况下自我定位。哪些知识是有用的,哪些手段会带来成功?为了这个目的,就必须详细分析材料文化的状况,建筑师必须形成对技艺的认识。因为没有实施项目的人就不可能创造出好的建筑。所以,找到既有传统知识、又愿意学习可以纳入其规范的新东西的工匠就是极为重要的。具有真实性的东西在传统建筑上不过是由工匠、所用的材料以及人们日常生活的文脉创造出来的,如今却不得不费尽心机去制造,而且需要恰当的维护。然而,社会的碎片已变得多元、混杂,这就是为何需要特别的考虑才能让建筑的作用不只是承载功能的空间。建筑师与客户进行理念上的协调是需要坚持的,有时甚至要改变最初的设想。因为不论谁在创新时,迈出第一步都是孤独的,否则那就不是新的了。

张轲结合城乡文脉的作品

如果有人要探索创新,就必须了解历史,并对新的需求有概念。张轲在与清华的学生探讨一个项目时问道:“我们可以将田园生活带到城市中吗?我们可以在乡村创造出城市的舒适度吗?我们可以找到一条结合二者优势的替代之路吗?”他在这里涉及到了对当代建筑举足轻重的一些因素,而这不只是针对中国。不过,这些价值如何在给定条件下成立的问题便出现了。

张轲和标准营造完成的建筑有的位于大都市中心,有的在疏于发展数十年的偏远地区。这就带来了如何利用设计的手段在如此多样的环境中抉择的问题。张轲在各地要面对不同的建造目标。在北京是老合院建筑的翻新,在上海是新办公建筑的未来,而在乡村地区是以当地材料和现存技艺为基础的新建筑。但他对项目总会从文脉出发,这在下文将进行评述:在北京,翻新是以给现存建筑增加当代使用的新要素为基础的;在上海,建筑井然屹立在周边校园的环境中;而在西藏或广西的风景环境中,天然地形成了干预工作的出发点。这些特征在不同程度上也可以用在其他项目上。即使是事务所在北京城墙遗址上的最初项目,也体现出这种利用文脉并促发一种历史性叙事的态度。这种叙事通过建筑的手段使建立认同并对其进行反思成为可能。对残破城墙的悉心保护不仅让人们看到城墙的悠久历史,还有1960-1970 年代经济与发展处于低谷的艰苦。标准营造创造了一种纪念建筑,让人回忆起错综的历史过程,并展示出在北京城墙最后残迹中承载的诸多层次。利用遗迹“原状”的思路可以作为1950 年代以彼得和艾莉森·史密森事务所为中心的英国建筑师与艺术家圈子所提出概念的变化形式来讨论。这种叙事的促发在重要性问题上是至关重要的一点,而这无疑必须对当地人和游客都保持可读、可阐释的状态。

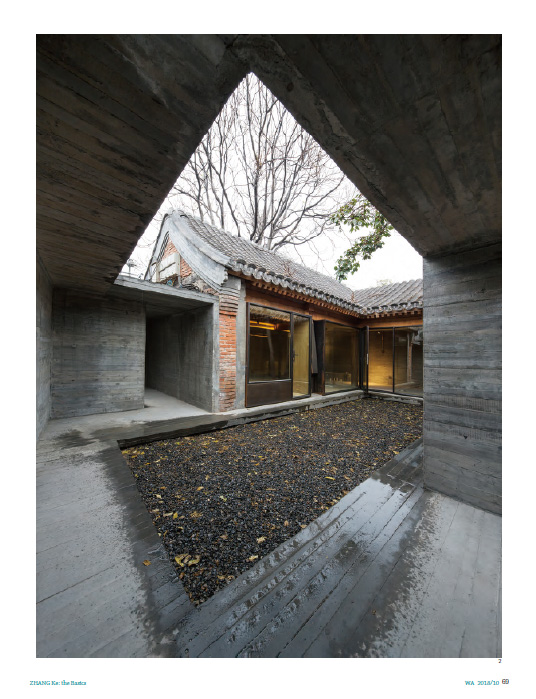

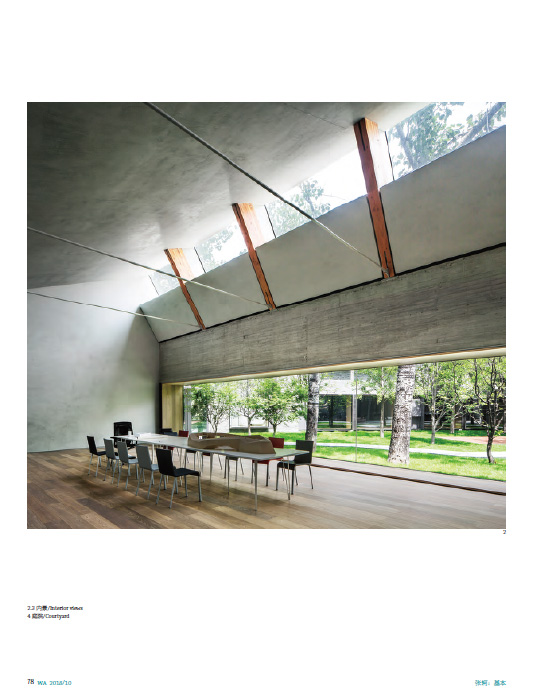

诺华上海园区

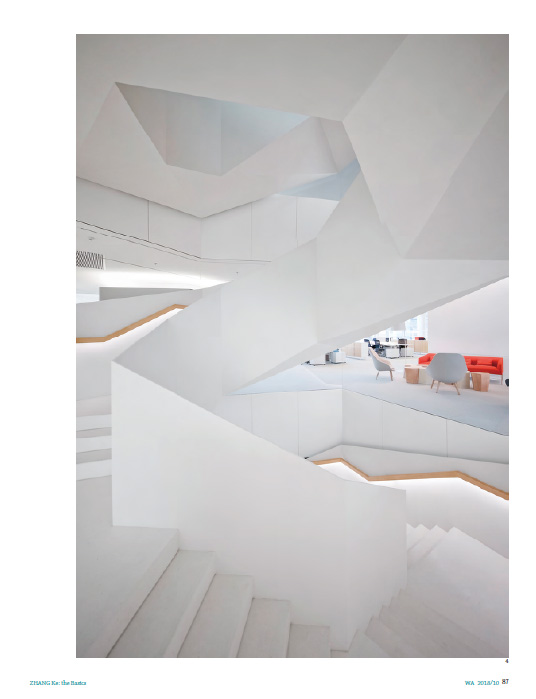

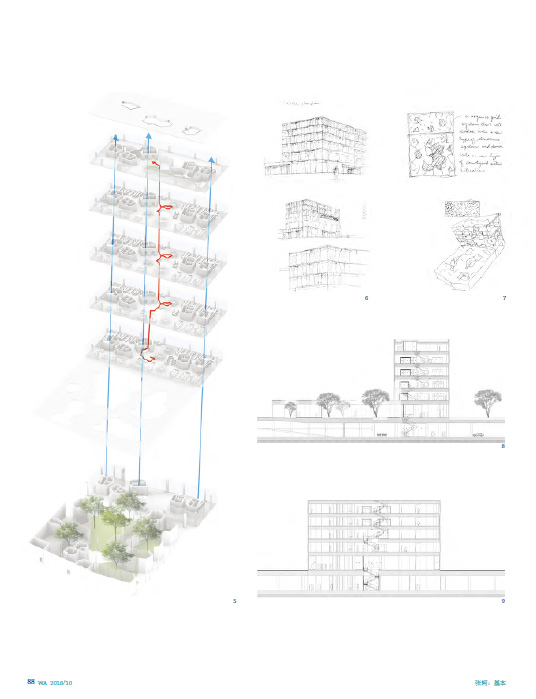

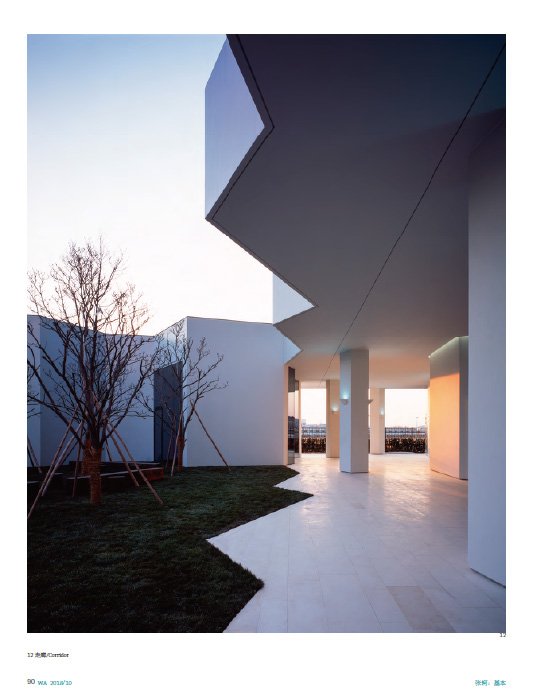

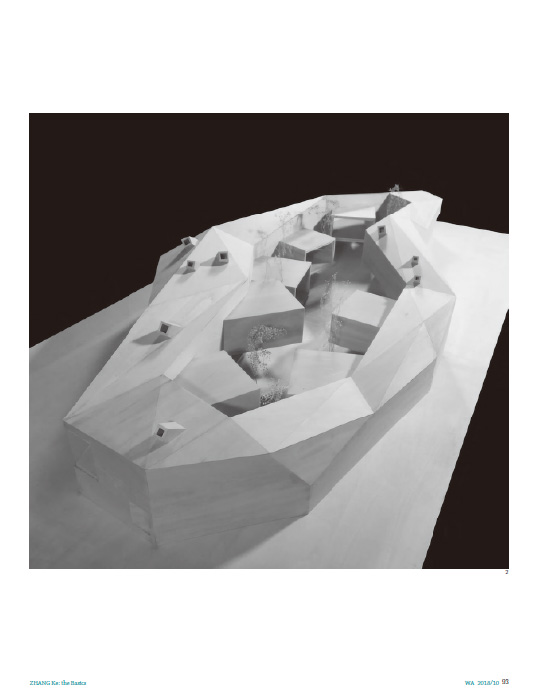

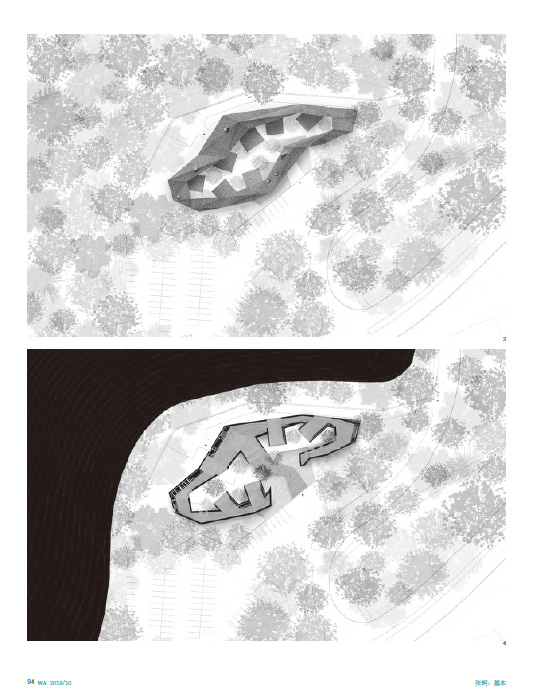

多位建筑师,包括刘家琨、隈研吾、张永和、亚历杭德罗·阿拉维纳、张轲与迪纳和迪纳建筑事务所,以及参与景观建筑的West8 事务所,建造了诺华上海园区。园区位于浦东,在市中心与浦东机场之间连接黄浦江与长江的笔直的川杨河从这里流过。这家全球化的瑞士制药公司将研发中心建在那里,并要满足质量要求,让建筑推动员工之间的创新性交流。这座6 层的办公楼在长方形的场地中有一个单层的延伸部分,其中有可变的工作空间,每层都构成了各自的特色。设计以单元网格为基础,其空间形式是从中国传统园林设计中获得灵感的。单层的部分嵌入了合院,它以多边形的基本元素为基础,并体现在蜿蜒楼台的造型上。这些合院的特色在于植物和表面覆板,它们与多边形的空间审美和主体建筑的玻璃立面形成了平和的对比。这个立面也受到了设计的基本单元规则的影响,并带有从远处便可产生炫目表面的倾斜要素。

主体建筑以不规则的柱网和多边形的核心空间为支撑,并留出大量可供个性化布置的自由办公空间。封闭的核心房是附属用房和电梯。弯曲的螺旋形开敞楼梯将各层连接在一起,犹如一座动感十足的雕塑。第二层到第五层有250 多个工位,还有会议室和交流区——在第六层还有更多。

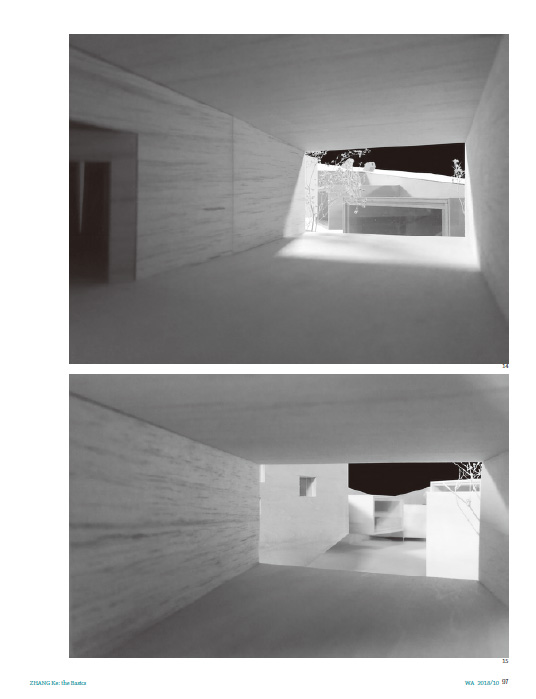

地面层有露天通道、小露台和亭状设施,让人联想到一种富有人性的城市景观,可以徒步去感受,并构成了通向研发的创新世界的道路。设计的高品质在狭小的工作环境中创造出一种如画的世界,以不生搬硬套的当代方式体现出多重历史价值。楼面、墙面和天花的实体要素以白色和灰色为主,与木家具或楼梯的木扶手形成了对比。室内外相互交融,并以贯穿地面层多个区域的楼面覆板为支撑。这样,介于景观与城市之间的世界便被悬置,并因办公楼高耸、通透的结构中的有机内在而改变。

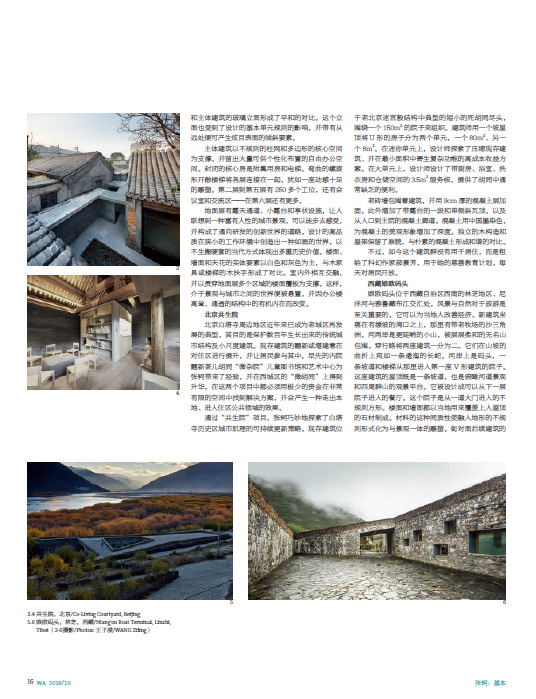

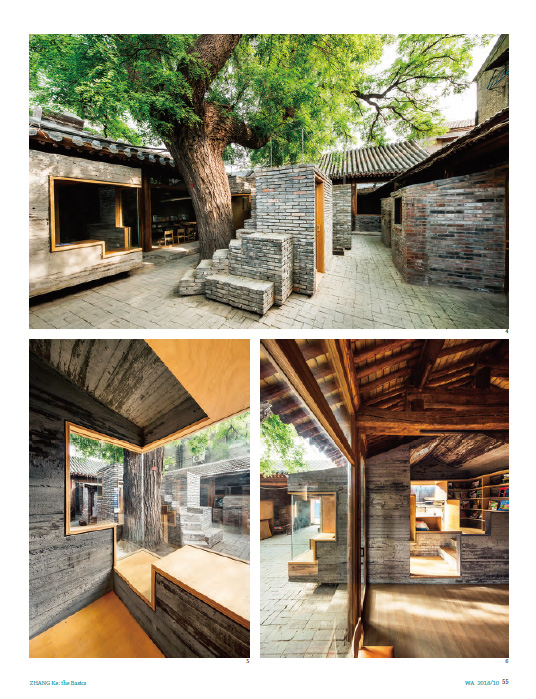

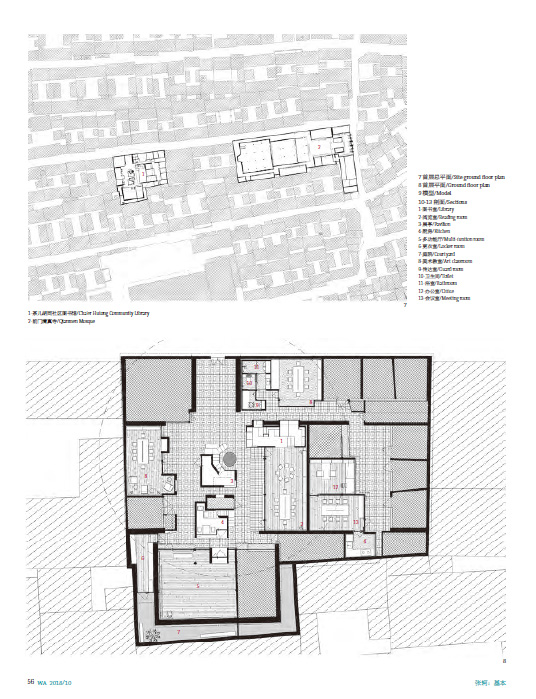

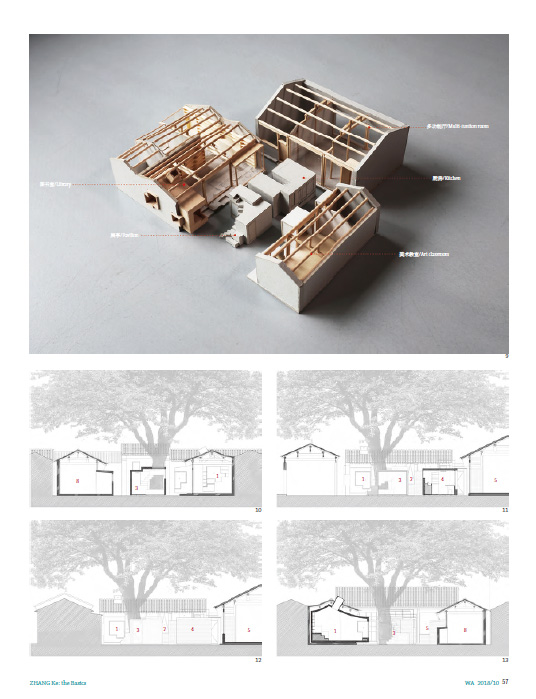

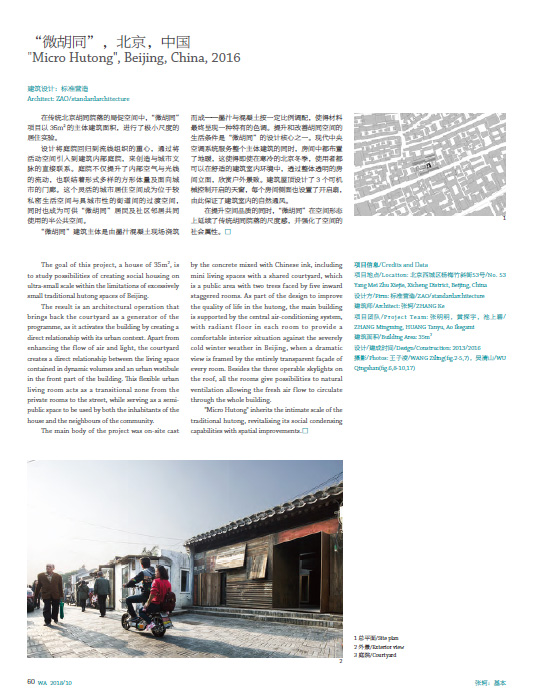

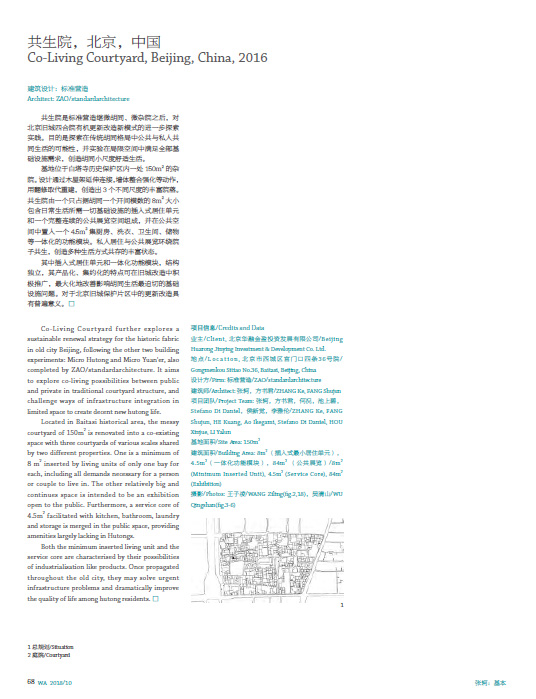

北京共生院

北京白塔寺周边地区近年来已成为老城区再发展的典型,其目的是保护数百年生长出来的传统城市结构及小尺度建筑。现存建筑的翻新或增建意在对住区进行提升,并让居民参与其中。早先的内院翻新茶儿胡同“微杂院”儿童图书馆和艺术中心为张轲带来了经验,并在西城区的“微胡同”上得到升华。在这两个项目中都必须用极少的资金在非常有限的空间中找到解决方案,并会产生一种走出本地、进入住区公共领域的效果。

通过“共生院”项目,张轲巧妙地探索了白塔寺历史区城市肌理的可持续更新策略。现存建筑位于老北京迷宫般结构中典型的短小的死胡同尽头,围绕一个150㎡ 的院子来组织。建筑师用一个坡屋顶将U 形的房子分为两个单元,一个80㎡ 、另一个8㎡ 。在迷你单元上,设计师探索了压缩现存建筑、并在最小面积中寄生复杂功能的高成本收益方案。在大单元上,设计师设计了带厨房、浴室、洗衣房和仓储空间的3.5㎡ 服务核,提供了胡同中通常缺乏的便利。

老砖墙包围着建筑,并用9cm 厚的混凝土层加固。此外增加了带露台的一段和单侧斜瓦顶,以及从入口到主院的混凝土廊道。混凝土用中国墨染色,为混凝土的美观形象增加了深度。独立的木构造和屋架保留了原貌,与朴素的混凝土形成和谐的对比。

不过,如今这个建筑群没有用于居住,而是租给了科幻作家郝景芳,用于她的慈善教育计划,每天对居民开放。

西藏娘欧码头

娘欧码头位于西藏自治区西南的林芝地区、尼洋河与雅鲁藏布江交汇处。风景与自然对于旅游是至关重要的,它可以为当地人改善经济。新建筑坐落在有缓坡的湾口之上,那里有带老牧场的沙三角洲。河两岸是更陡峭的小山,被层层柔和的无名山包围。穿行路将两座建筑一分为二。它们在山坡的曲折上宛如一条逶迤的长蛇。河岸上是码头,一条坡道和楼梯从那里进入第一座V 形建筑的院子。这座建筑的屋顶既是一条坡道,也是俯瞰河道景观和四周群山的观景平台。它被设计成可以从下一层院子进入的餐厅。这个院子是从一道大门进入的不规则方形。楼面和墙面都以当地用来覆盖上人屋顶的石材制成。材料的这种同质性使融入地形的不规则形式化为与景观一体的雕塑。街对面后续建筑的曲折形首先构成了一个二维平面,作为公共汽车场,而后在坡上是一个轿车场。下一个V 形建筑有一座简单的酒店,屋顶上的坡道通往山坡上。这个曲折的建筑群以一座小平台上的建筑为终点,在那里远眺山谷和码头的视线可以伸向远方。酒店和坡道都覆盖相同的当地石材,更强化了雕塑的印象,并使建筑形式超越了功能,而接近大地艺术。餐厅部分没有用扶手,而是沿坡道堆放木柴外皮,将喜马拉雅山恶劣气候中的老化过程更清晰地展现出来。当地石材和木皮的简约以其独特性强化了雕塑的特征。

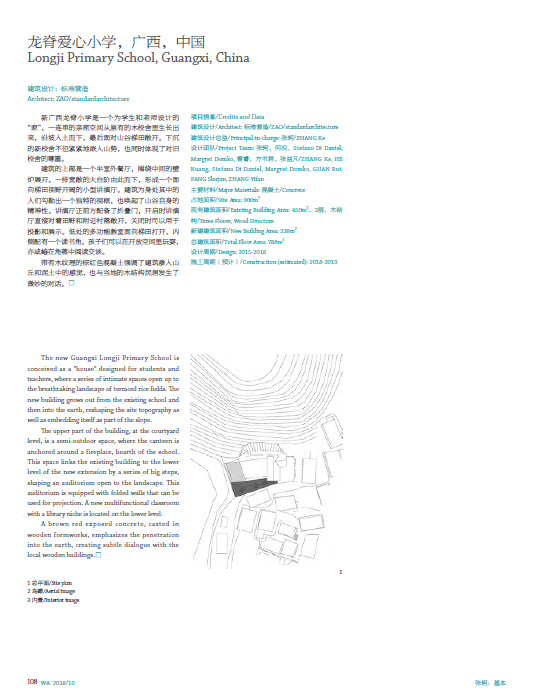

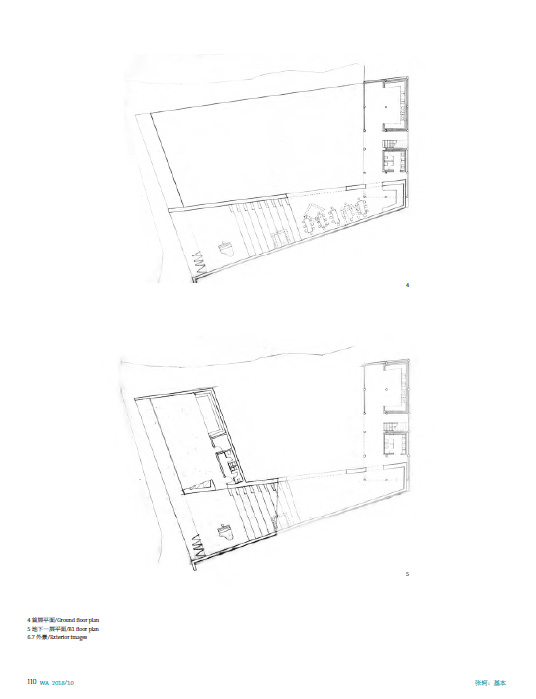

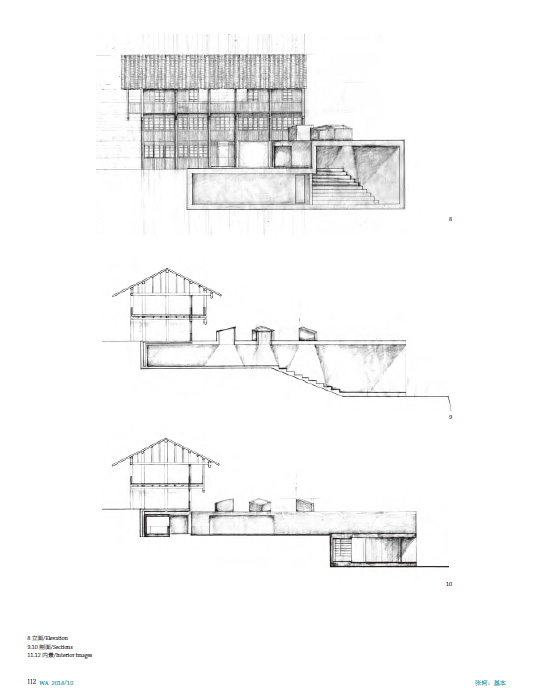

广西龙脊小学

中国西南的广西自治区毗邻越南,是相对贫困的一个省,但有丰富的文化和动人的景观。那里有很大的自然发展潜力,但它需要创意、技能和教育。龙脊小学的新设计是标准营造给当地儿童的馈赠。如今他们在一座见证了更好时期的3 层坡屋顶木建筑里上学。这座L 形的建筑质量在所有教学建筑的标准之下。然而,没有高质量的建筑,就无法找到优秀的教师,而孩子们就没有机会发展自己的天赋。

现存的建筑屹立在谷底的坡地上,从那里可以俯瞰整个地区的梯田。山的一侧是带木屋的传统村落,山在另一侧耸立于梯田之上。在这个露天的位置上,建筑与地形条件紧密相联。这个新设计在底部为师生提供了厨房。它嵌在山坡里,面向校园。在此之上木建筑有2 层楼,每个有3间教室,由中间的开敞楼梯进入。底部靠近厨房的地方是新的开敞式侧楼。它在同一个层高上,由棕红色混凝土建成,利用地形设计了可坐人的楼梯,并在下端与带小图书馆的多功能教室连接起来。可坐人的楼梯面朝景观,并能用折叠门封闭起来,举行活动。在现存木建筑与新的混凝土扩建部之间的角上有一个开敞的壁炉,让人想到有2 根木柱、并与食堂一体的主建筑。上方的平屋顶构有光柱,在室内形成了蜿蜒的光斑。真正的挑战将出现在现存建筑翻新、新建筑建成之时。众筹保证了所需的资金,而村中孩子们的未来成了城市人的事。人群的联系对于建立共同的认识以及公开社会内的责任都非常重要。

结语

如果依次回顾一下上文介绍的4 个优秀项目,就会看到张轲每次都有意识地将环境作为探讨的出发点。首要的问题不在于审美决策,而是预期的用途、城市或景观设计的挑战,以及对决定结果的技艺的思考。尽管如此,这是一种独立审美的产物,它将对全球建筑话语的借鉴与地方刺激结合起来。他在这里的创作将美国的教育与中国作品各地的条件融合在一起。

如果考察一下偏远地区的建筑,就可以看到一种强烈的材料文化。它首先展示出人创作的过程,例如对石材的加工。粗野的表达成了一种指引人们认同的风格化手段。学校、码头或博物馆等公共建筑尤其适合于此,因为它们用一种当代手法与一个地区普遍的表面化传统借鉴方式形成了反差。这些粗野的手法利用了粗野主义中最好的东西,并以阐释空间创造出一种混合结果。建筑与自然地形和尺度的结合使它们成为乡村当代表达的典范项目。材料文化中微妙的粗野主义手法与粗野审美结合起来,限定出一种植根于当地的处理方式。只要使用者将这个结果理解为一种对他们认同的真实表达,那它如何得出的问题就是无关紧要的。

诺华园区建筑柔顺、雅致的外观与粗野手法相对立,尽管其基本设计思路也植根于一种利用历史既成形式的思想。虽然传统住区和偏远地区的设计思路更多地以简约为主,并且建筑是针对材料文化的;但在像诺华园区这样的新建筑上,与历史的呼应被转化为一种当代城市材料的文化。这里形成了一个闭环,以当地情况和使用者的需求作为出发点,将环境小心地转化为一种建立认同的建筑文化的新体系,不论在城市中心还是乡村景观。

当然,对乡村现存构筑物或建筑的小型干预也带来了成本的问题。一方面资金极其有限;另一方面审批过程会更简单,并且无需与城市相同的标准。但是,最小干预的简化与节约成本毫无关系,而需要的是一种在看似令人费解的“一切皆有可能”的态度。认同会在人们积极参与并能为他们的未来愿景负责的情况下形成。对于建筑师,这就意味着积极为可理解的审美努力,它会给居民带来一种自豪感和自信。

开篇所描述的扭曲现象对于仅仅利用历史的认同是不必要的,而当代建筑可以为一种不仅可以接受,而且能全面满足各种需求的环境作出它的贡献。

建筑师很难摆脱社会中的各种潮流和时尚。要意识到这一点并寻找有助于建立当代真实性的解决之道,比所有的荣誉都更有价值——因为这会帮助人们从历史的眷恋和转变走向与未来的对话。在本文讨论的张轲作品中,有一点是明确的:促发这种讨论是值得的。每个项目都必须找到它的独特方式,使建筑不仅在建成之日后作为时间的标记是可读的,同时还让它的老化能符合建筑材料和社会的需求。建筑只是一种工具和建造条件的见证,但在未来它还会揭示出创造了这些建筑的社会的各种渴求与希望。

The historical building culture still shapes China's popular national identity today. There is no brochure or advertising material without curved roofs or pagodas. An additional narrative has been added in recent years: the generic skyscraper city, which provides a background for the curved roofs and historical variety of forms without any local reference. However, the city of the people has lost its simple identity-creating frame of reference from the living environment. Not only functionally one-dimensional city quarters, but also aesthetically impoverished concepts complicate identification and thus the sense of responsibility for the neighbourhood. But what does a contemporary environment look like that is accepted and cared for by the population?

In the case of large cultural buildings, the form and the public mandate for maintenance may have a symbolic effect, but in the case of small-scale everyday culture the true meaning of an architectural intervention can be seen. The question of how architects understand their job and what significance they attach to the context they find is of paramount importance alongside the intensive discourse with the users. For an identity-forming architecture does not emerge on the drawing board, but needs advocates and defenders against the everyday signs of decay of all materials.

In today's world, which is very much characterised by superficial appearances, architecture also shines in a dazzling outfit that can't age but breaks. This is certainly one reason why it has become difficult to understand architecture as a culture supported by the population through an emotional bond. Because without the material remains the form, which can also be very arbitrary. A supposedly avant-garde building can end up on the rubbish heap of history so quickly and its symbolic power has already been exhausted with its completion.

The question therefore remains to the architect as to how he should position himself under the given circumstances. Which knowledge is useful and which measures promise success? To this end, the situation of the material culture must be analysed in detail and the architect must develop an understanding of craftsman ship. Because without the people who have to implement a project, no good architecture can be created. It is therefore extremely important to find craftsmen who on the one hand have traditional knowledge and at the same time are willing to learn new things that can be integrated into their canon. The authentic, which in traditional architecture was created simply by the craftsmen, the materials used and from the everyday living context of the population, has to be painstakingly produced today and then requires proper care. However, the social mosaic of society has become diverse and hybrid, which is why special considerations are needed to make a building task more than just a space in which functions are inscribed. It takes commitment for the architect to harmonise his ideas with those of the client, sometimes even against his original ideas. Because whoever does something new is always alone in the first step, otherwise it would not be new.

ZHANG Ke's Work in the Urban and the Rural Context

If someone is looking for the new, he must know the old and develop an idea of what is needed. ZHANG Ke asked for a project with students of Tsinghua University: "Can we bring bucolic life into the city? Can we create urban comfort in the countryside? Or can we find a novel alternative that combines the advantages of both sides?" He addresses here some aspects that are important for contemporary architecture not only in the Chinese context. However, the question arises as to how these values are possible under the given conditions.

The buildings ZHANG Ke and his firm ZAO/standardarchitecture erected are located both in the centre of the large metropolises and in the distant hinterland, where developments have been neglected for decades. This leads to the question of how one can act in such diverse environments with the means of design. Within the different locations, ZHANG Ke dealt with various construction tasks. In Beijing with renovations of old courtyard buildings, in Shanghai with the future of office work in a new building and in the rural area with new buildings based on local materials and existing craftsmanship. But he always behaves contextually with his projects, which are under review below: In Beijing the renovation is based on the existing building with additional elements for contemporary use, in Shanghai the building sits disciplined in the context of the surrounding campus and in the scenic context of Tibet or Guangxi the direct topography became the starting point of the intervention. These attributes can also be applied to other projects to varying degrees. Even the very first project of the office for the remains of the city wall in Beijing showed this attitude of bringing the context to speak and thus stimulating a historical narrative which, with the means of architecture, makes it possible to identify and reconsider identity. The careful preservation of the crumbling city wall not only reminds people about the long history of the wall, but also about the hardship of the 1960s and 1970s, when the economy and development generally were at their lowest points. ZAO/standardarchitecture created a monument that calls the complex historic process to mind and reports on the different layers embodied in the last section of the city wall of Beijing. The strategy to use the ruin "as found" can be discussed as a variation of the concept developed by the circle of British architects and artists centred around Peter and Alison Smithson in the 1950s. The stimulation of the narrative is an essential point in the question of importance, which of course must remain readable and interpretable for the local population and visitors.

Novartis Campus Building in Shanghai

Many different architects, including LIU Jiakun, Kengo Kuma, Yung Ho Chang, Alejandro Aravena, ZHANG Ke and Diener & Diener, with West 8 as one of the landscape architects, built the Novartis Campus in Shanghai. The campus is located in Pudong halfway between the city centre and the airport on the linear Chuanyang River, which connects the Huangpu River with the Yangtze River. The globalised Swiss pharmaceutical company built a research and development centre there that had to meet its own quality requirements and whose architecture promotes innovative communication among its employees. The six-storey office building with a one-storey extension on a rectangular site contains flexible workplaces, which are differently composed with individual characteristics on each floor. The design is based on a cellular grid, which is inspired in its spatial form by traditional Chinese garden design. In the single-storey part, courtyards are cut in, which are based on polygonal basic elements and are also reflected in the shape of the meandering pavilions. The courtyards are characterised by the planting and the surface covering, which provide a calming contrast to the polygonal aesthetics of the spaces and the glass façade of the main building. The façade is also influenced by the basic cellular principles of the design and consists of tilted elements that evoke a dazzling surface from a distance.

The main building is supported by an irregular column grid and polygonal core spaces, which leave a lot of free office space for individual arrangement. The closed core rooms are for ancillary rooms and elevators, while the meandering spiral-shaped open staircase connects the floors like a dynamic sculpture. From the 2nd to the 5th floor there are over 250 workstations with meeting rooms and communication zones, with further meeting rooms and communication zones on the 6th floor.

The ground floor, with its open passages, small patios and pavilion-like fixtures, is reminiscent of a humane urban landscape that can be experienced on foot and structures access to an innovative world of research and development. The high quality of the design creates a pictorial world in the narrow context of the working environment that reflects historical values in a contemporary way without making formal copies. The solid components of the floor, wall and ceiling are dominated by the colours white and grey, which are contrasted by wooden furniture or wooden handrails of the staircase. Inside and outside merge into each other, which is supported by the floor covering that runs through a number of areas on the ground floor. The intermediate world between landscape and city thus remains in abeyance and is transformed by the towering crystalline structure of the offices in its organic priming.

Co-living Courtyard in Beijing

The area around the Baitasi Pagoda in Beijing has in recent years become a case of redevelopment, in which the traditional urban structure, which has grown over centuries, is to be preserved with its small-scale buildings. The new renovations or additions to existing buildings are deliberately intended to enhance the quarter and involve the residents. The earlier renovation of an inner courtyard of the "Micro Yuan'er" children's library and art centre in Cha'er Hutong brought ZHANG Ke some experiences that were intensified with "Micro Hutong" in Xicheng district. In both cases, a solution had to be found in a very confined space with little money, which would also have an effect beyond the location into the public sphere of the neighbourhood.

With the project for the "Co-living Courtyard", ZHANG Ke subtly explores a sustainable renewal strategy for the urban fabric in the historic area of Baitasi. The existing building is located at the end of a short cul-de-sac typical of the labyrinthine structure of ancient Beijing and is organized around a 150㎡ courtyard. The architects divided the U-formed house with a pitched roof into two units, one with 80㎡ and second one with 8㎡. With the mini unit, the designers are looking for a cost-effective solution for compacting the existing structure and parasitically nesting a functionally sophisticated use in the minimised area. For the larger unit, the designers developed a 3.5㎡ service core with kitchen, bathroom, laundry and storage space that offers the amenities that are largely lacking in the Hutongs.

The historic brick wall surrounds the property and was reinforced with a nine centimetre thick concrete layer. A segment with a patio and a one-sided inclined tiled roof was added, as well as a covered concrete path leading from the entrance to the main courtyard. The concrete is dyed with Chinese ink, which adds depth to the aesthetic appearance of the concrete. The freestanding wooden construction and the roof substructure have been left in their natural appearance, creating a harmonious contrast to austere concrete.

Today, however, the ensemble is not used as a residential building, but was rented by the science fiction writer HAO Jingfang for her charity education program and is open every day for the residents.

Niang'ou Boat Terminal in Tibet

The Niang'ou Terminal is located in the Linzhi District in the southwest of the Tibet Autonomous Region, where the Niyang and the Yarlung Zangbo Rivers meet. The landscape and nature are important for tourism, which should bring an economic improvement for the local population. The new building is situated above a gently sloping bay with old pastures on a sand delta. On the banks of the river there are steeper hills, framed in layers by soft, nameless mountains. The through road separates the composition of two buildings. Both together develop like a continuous snake in the zigzag up the slope. On the bank of the river there is the boat dock, from which a ramp and stairs develop into the courtyard of the first V-shaped building. The roof of the first building is both a ramp and a viewing platform overlooking the river landscape and the surrounding mountains. The building is designed as a restaurant accessible from the courtyard one level below. The courtyard is an irregular square entered through a gate. The floor and walls are made of the same local stone that was used to cover the walk-in roof. This homogeneity of the material transforms the irregular form fitted into the topography into a sculpture that merges with the landscape. The zigzag figure of the further construction beyond the street first develops in a two-dimensional plane as a bus parking area and then as a car park up the slope. The next V-shaped building contains a simple hotel, over whose roof the ramp leads further up the slope. The zigzag complex ends above the buildings in a small platform from where the view over the valley and the pier can wander into the distance. The hotel and the ramps are also clad in the same locally available stone, which further reinforces the impression of a sculpture and moves the building form beyond its function into the vicinity of Land Art projects. In the restaurant section, instead of a railing, firewood sheath was piled up along the ramps to bring out the aging process even more clearly in the harsh climate of the Himalayas. The reduction of the local stone and the wooden sheath reinforces the sculptural character with its uniqueness.

Longji Primary School in Guangxi

The Autonomous Region Guangxi in the southwest of China at the boarder to Vietnam is rather one of the poor provinces, but it has a rich culture and an impressive landscape. There is a lot of natural potential for development, but it needs ideas, know-how and education. The new planning for the Longji Primary School is a gift from ZAO/standardarchitecture to the children there. Today they are taught in a three-storey wooden building with pitched roof that has seen better times. The quality of the L-shaped building falls below all standards for teaching buildings. Without a high quality building, however, no good teaching staff can be found and the children have little opportunity to develop their talents.

The existing building stands in a valley floor on a slope from where the view can wander over the terraced rice fields of the region. On one side of the hill is the traditional village with its wooden houses, on the other side the hill rises above the terraces for the rice fields. In this exposed location, the building is closely linked to the topographical conditions. The new design provides for a kitchen for the pupils and teachers in the basement, which is pushed into the slope and opens onto the schoolyard. Above this there are two floors in the wooden building, each with three classrooms, which are accessed by an open staircase in the middle. Next to the kitchen in the basement is a new open side wing in reddish brown concrete on the same level, which exploits the topography via a seating staircase and at the lower end merges into a multifunctional classroom with a small library. The seated staircase opens onto the landscape and can be closed by a folding door for events. In the corner between the existing wooden building and the new concrete addition there is an open fireplace, which is reminiscent of the main building with two wooden columns, and which then merges into the canteen. The flat roof above is structured by the light cannons, which create a wandering sunspot inside. The real challenge will come when the existing building is renovated and the new building is built. With crowdfunding, the money needed is secured and the future of the children in the village becomes a matter for the urban population. The connection of the population groups is important to make a mutual understanding, but also responsibility within society visible.

Conclusion

If we look at the four outstanding projects described above one after the other, we can see that ZHANG Ke very consciously makes the respective environment the starting point of his discussion. It is not primarily a question of aesthetic decisions, but of the intended use, urban or landscape planning challenges and reflection on craftsmanship that determine the result. Nevertheless, this results in an independent aesthetic that combines borrowings from global architectural discourses with local stimuli. His own career here combines with training and teaching in the USA and the conditions in the respective places in China where the works are located.

If we take a look at the buildings in the hinterland, we can see a strong material culture, which above all leaves the human working process visible, for example in stone processing. The rustic expression becomes a stylistic device that can orient the identity of the population. Public buildings such as schools, boat docks or museums are particularly suitable for this, because they counteract the ubiquitous superficial traditional reference of a region with a contemporary touch. These rustic manners employ aspects of brutalism in its best sense, and create a hybrid outcome with space for interpretation. The integration of the buildings into the natural topography and scale makes them reference-projects for a contemporary expression at village level. The approaches of subtle brutalism in material culture combined with rustic aesthetics help to define a locally rooted approximation. The question how the result came about seems not to be relevant, as long as the users understand the result as an authentic expression of their identity.

The smooth and elegant appearance of the Novartis building stands for the opposite of a rustic manner, although its basic design strategy is also anchored in a thinking that makes use of formal set pieces of history. While the design strategy in traditional neighbourhoods and the hinterland is more dominated by reduction and the architecture is oriented towards the culture of materials, in a new building such as Novartis the echoes of the past are translated into a contemporary urban culture of materials. Here, a circle closes that brings about the local situation and the needs of the users as a starting point for a cautious transformation of the environment into a new reference for identity-creating building culture; whether in the urban centre or in the rural landscape.

Of course, the small interventions in the existing structure or the buildings in the villages also raise a question of costs. On the one hand there is simply little money, on the other hand the approval processes are simpler and do not require the same standards as in the city. However, the reduction to the smallest possible intervention has nothing to do with cost savings, but with the preparation of an attitude in the formal gibberish of "anything is possible". Identity arises where the population is actively involved and where they can take responsibility for their vision of the future. For architects, this means actively working for a comprehensible aesthetic that gives the residents a sense of pride and confidence.

Then the contortions described at the beginning will be unnecessary for an identity that only makes use of history, and contemporary architecture can make its contribution to an environment that is not only acceptable, but can meet the needs in a comprehensive sense.

It is difficult for architects to escape the trends and fashions within society. To be aware of this and to look for solutions that nevertheless make a contribution to create a contemporary authenticity is worth more than all honours, because it helps from the nostalgia and transfiguration of history into a dialogue with the future. In the case of the works by ZHANG Ke discussed here, it becomes clear that it is worth stimulating this discourse. Each project must find its own way of making architecture readable beyond the day of completion as a signal of its time, while at the same time allowing it to age in accordance with the building material and social needs. Architecture is only a tool and a witness to the conditions in which it was built, but in the future it will also tell of the desires and hopes of the society in which these buildings were realised.

作者单位:爱德华·科格尔事务所工作室/Studio Eduard Koegel

收稿日期:2018-10-01

雅鲁藏布江小码头,林芝,西藏,中国

The Yarlung Zangbo Boat Terminal, Linzhi, Tibet, China, 2008

建筑设计:标准营造

Architect: ZAO/standardarchitecture

小码头位于西藏雅鲁藏布大峡谷南迦巴瓦雪山脚下的派镇附近,派镇是林芝地区米林县的一个村级小镇,不仅是雅鲁藏布大峡谷的入口,还因为是通往全国唯一不通公路的墨脱县的陆路转运站而早就成为终极徒步旅行者的胜地。自从大峡谷被认定为世界第一大峡谷、中国国家地理杂志将其中海拔7782m 的南迦巴瓦雪山选为“中国最美的山峰”之首,逐渐成为普通徒步旅行者的目的地。

设计是从地段的选择开始的。我们从派镇出发沿岸一路向下游方向寻找合适的位置,我们需要一块水流相对较缓同时有一定水深的河岸。走到大约2km 外的江面拐弯处,我们一眼看中了这个位置,这里有形态特别的4 棵胸径都超过1m 的大杨树,旁边还有几块巨大的岩石,站在岩石上顺着江流的方向看过去,随时可以看到峡谷背后高耸的加拉白垒和南迦巴瓦雪山。

码头的规模很小,只有430㎡,功能也很朴素,主要为水路往返的旅行者提供基本的休息、候船、卫生间及恶劣天气情况下临时过夜等功能。建筑是江边复杂地形的一部分,一条连续曲折的坡道,从江面开始沿岸向上,在几棵树之间曲折缠绕,坡道与两棵大树一起,围合成面向江面的小庭院,庭院由碎石铺成,可以供乘客休息观景。由庭院再向上,坡道先穿过上层坡道形成的一个挑空过道,经两次左转悬空越过自己,然后再次右转,并在高处从两棵大树之间穿出悬挑到江面上,成为一个飘在江面上的观景台。

码头的室内空间分为两部分,一块是候船厅,一块是售票室和守候人员临时卧室,分别利用地形和坡势,隐藏在坡道的下面。候船厅面对的是低一点的小庭院和两棵大杨树,厅内有供休息喝茶的条桌条凳和冬季烧火取暖的石头炉子,尽端是两个卫生间。售票室和临时卧室位于最高标高的坡道下面,是部分悬挑的部分,卧室外有木平台,从木平台上看出去有很好的视野,可以观察江面的船只情况和远处的加拉白垒雪山。

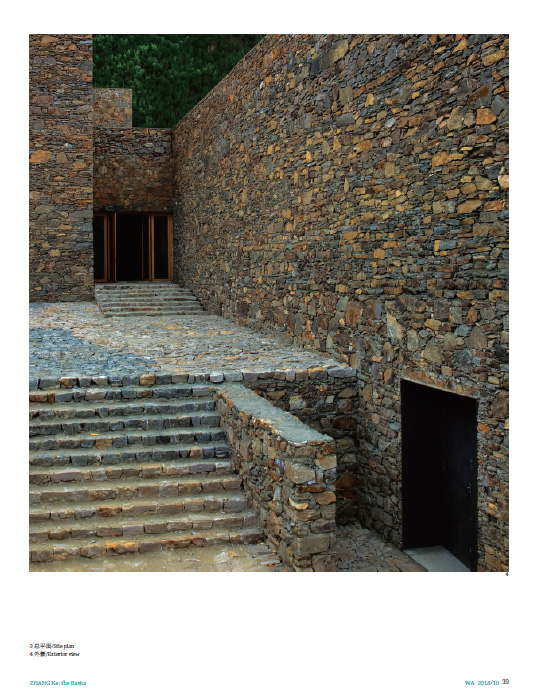

建筑的材料,从墙面到坡道的地面,全部是来自附近的石头,墙体的砌筑全部由当地工匠采用他们熟悉的方式完成,室外和室内都统一采用粗糙的石墙;门窗和室内的天花、地面自然是用当地松木以当地的方式在现场加工的。

The small boat terminal is located near to the small village named Pai Town in the prefecture of Linzhi in Tibet Autonomous Region. As the remotest stop along the Yarlung Zangbo River, it allows both local people and travelers from outside to transport by water deep into the valley and come to the foot of the Namchabarwa Snow Mountain.

With a total area of only 430㎡, the building programme is quite basic. It has a few toilets, a waiting lounge, a ticket office and a room for people to stay overnight in case the weather goes too fierce to travel on the river. The programmes are covered by a series of ramps rising from the water and winding around several big poplar trees, and ends up suspending over the water. Looking from a distance, the building is completely merged in the riverbank topography and becomes part of the greater landscape.

Construction materials are mainly local. All the walls and roofs are made of rocks collected from nearby. Walls are built by Tibetan masonry builders in their own pattern. Window and door frames, ceilings and floors are all made of local timber by a local method.

项目信息/Credits and Data

建筑设计/Architect: 标准营造/ZAO/standardarchitecture

设计团队/Design Team: 张轲,侯正华,张弘,Claudia Taborda,董丽娜,孙伟/ZHANG Ke, HOU Zhenghua, ZHANG Hong, Claudia Taborda, DONG Lina, SUN Wei

合作设计/Collaborate Design Institution: 中国建研建筑设计研究院,西藏有道建筑设计公司/China Academy of Building Research Architectural Design Institute, Tibet Youdao Architecture Associates

结构形式/Structural System: 石墙混凝土结构与局部钢结构混合/Mixed - Stone Masonry & Concrete Frame and Steel

项目功能/Program: 码头/Public Boat Terminal

基地面积/Site Area: 1000㎡

建筑面积/Building Area: 430㎡

设计时间/Design Period: 2007

施工时间/Construction Period: 2008

摄影/Photos: 王子凌/WANG Ziling(fig.1,2,10),陈溯/CHEN Su(fig.6,11,12),标准营造/ZAO/standardarchitecture(fig.7)

评论

王硕:2006年,标准营造开始为雅鲁藏布江河谷地区旅游产业进行一系列基础设施建筑的规划。这一系列项目的契机是林芝地区落成了一座机场。而随着雅鲁藏布江大峡谷被认定为“世界第一大峡谷”、南迦巴瓦雪山被选为“中国最美的山峰”之首,这里逐渐成为徒步旅行者的目的地。派镇作为整个雅鲁藏布江大峡谷景区的起始点,往下游不远处的小码头是张轲西藏系列建造的第一个,有着特别的开端意义。

整个建筑几乎就是由一条从河岸延升上来的连续而曲折的坡道定义而成的。顺着这条无尽折叠的坡道,可以从停靠的船舶开始,途经建筑两块基本的功能:候船厅和售票室,并从其间穿越而过,进而转身从坡道走上屋面越过自己的头顶……一路走来,仿佛布达拉宫前绵长曲折的台阶,在露台上望向同样蜿蜒盘旋的江面,建筑的存在反而不再是关注点。通过顺应地势的扭转倾斜,建筑很好地嵌入了周边的地形,与它背靠的山崖融为一体,包括建筑外立面所使用的本地石材、木材及本地工艺,都明确地指向了这一设计所采取的基本策略,即与周围的自然环境及文化由一种平视的角度谋求新的契合点。

平视并不等于平淡。整座建筑的体验中有两个“悬浮的时刻”,分别对应两个方向的到访者。第一个在来路方向建筑形体的锐角处,这里建筑被切削成很薄的悬挑;第二个则是连续坡道的尽端——面向江面悬挑而出的有阳台开口的眺望空间。这一悬浮的建筑体量与周边层叠厚重的挡土墙以及浓茂的山林产生了一种精巧的反差,从江中看去,小码头既融入环境又跳出背景。这不由让人想到罗伯特·史密森的“螺旋防波堤”,小码头仿佛一个随时要消失的地景标志建筑 ——“Land(scape) Mark”,只在地景中留下一个轻巧的痕迹。

从“平视”的角度出发,藉由建造所呈现出来的“悬浮”感,小码头创造了新的形式逻辑,打破了藏区近年来形成的用新材料模仿藏族风格建筑的定式,不去破坏当地文化的本真。张轲所提出的介入策略,将关注点放在如何使“中国的当代性”这一新的时代价值最大化——通过削减重量,抬升到一种很轻的悬浮状态。这种悬浮,既是操作层面的,也是视觉层面的。从当代空间生产角度而言,他引出的实践方向具有双重穿透性。这些建筑物/ 空间在当地藏族人看来与传统不是同质化的,于本地建成环境而言有一种蜻蜓点水的跳脱感;而从旅行者来看,它又深刻地镶嵌在周边环境和文化中,仿佛是从地景中生长出来的“水晶”。

如果说标准营造第一个5 年的实践实现了一种在中国多变的城市环境中对设计品质的“现代性”革新追求,那么从雅鲁藏布江小码头开始展开西藏系列实践的张轲,已经更加能够自由并打破“现代性”既定标准地来进行空间实践了。用他自己的话来说,已成为“标准的对立面,目标就是打破现有标准”。至此,张轲从具有“普遍性”的城市中跳转到更有“特定性”自然环境/ 文化传统的地区,并由此展开了一系列具有积极的“当代性” 意义的空间生产探索。

Comment

WANG Shuo: In the year 2006, ZAO began to plan a series of infrastructure buildings for the tourism industry in the valley area of Yarlung Zangbo River. The opportunity for this series of projects is a result of a recently completed airport in Linzhi. Since the Yarlung Zangbo River Grand Canyon was recognised as the world's largest canyon, and the Namchabarwa Mountain was chosen as the first among the "most beautiful peaks in China," it has gradually become a hikers' destination. The little boat terminal not far downstream from Pai Town, the starting point of the whole scenic area of the Yarlung Zangbo River Grand Canyon, is the first of ZHANG Ke's Tibetan construction series, and has a special significance of beginning.

The whole building is almost simply defined by a continuous zigzagged ramp extending and rising from the riverbank. Going from the anchored boats along this endlessly folding ramp, you can pass by two basic functional areas of the building: the waiting room and the ticket office. After walking through between them, visitors turn and walk up the ramp to the roof and over your head... all the way up like the long zigzagged staircase in front of the Potala Palace. When they are looking at the similar winding river from the balcony, the existence of the building is no longer a concern. By adjusting to the twisting and sloping of the ground, the building is well embedded in the surrounding terrain and blends with the cliffs against its back, and all the local stone, timber and local craftsmanship used on the facades of the building also clearly point to this basic strategy of the design, namely, to reach a new harmony with the surrounding natural environment and culture in a "horizontal view".

The horizontal view does not equal to plain. There are two "moments of levitation" in the building experience that correspond respectively to visitors from the two directions. The first one is at the sharp corner of the building in the direction of arrival, where the building is cut into a very thin overhang. The second is at the end of the continuous ramp – a lookout space reaching out towards the river with balcony openings. This "suspended" building volume forms a delicate contrast to the heavy layers of retaining walls and lush forests around it. Looking from the river, the boat terminal is both melting into the environment and standing out from the background. Reminding people of Robert Smithson's Spiral Jetty , the boat terminal is like a land(scape) mark that's going to disappear at any moment, leaving only a light trace in the landscape.

From the perspective of "level view", with the sense of "levitation" presented by the construction, the boat terminal has created a new kind of form logic, breaking the formula of imitating Tibetan style architecture with new materials, which was formed in the Tibetan region in recent years, without destroying the authenticity of the local culture. The intervention strategy ZHANG Ke put forward focuses on how to maximise "Chinese Modernism", the value of the new era, by reducing weight and lifting up to a very light "levitation" state. This levitation is both operational and visual. From the perspective of contemporary space production, the direction of practice he points out has cross-penetration. From the local Tibetans' point of view, these buildings/spaces are not homogeneous with the tradition, so there is a sense of aloofness from the local built environment like "dragonfly on water"; and from the travelers' point of view, it is deeply embedded in the surrounding environment and culture, as if it's a "crystal" growing out of the landscape.

If it could be said that ZAO's first 5 years of practice has realised a "modernity" in the pursuit of innovation and design quality in constantly changing urban environment in China, then from the Tibetan practices beginning with the Yarlung Zangbo River Boat Terminal, ZHANG Ke has become more free and able to break the established standards of "modernity" to carry out space practices. In his own words, he has become the "antithesis of standard, and the goal is to break the existing standards". So far, ZHANG Ke has jumped from cities of "universality" to regions with more "specificality" in natural environment/cultural tradition, and thus launched a series of space production exploration with positive significance of "modernity". (Translated by CHEN Yuxiao)

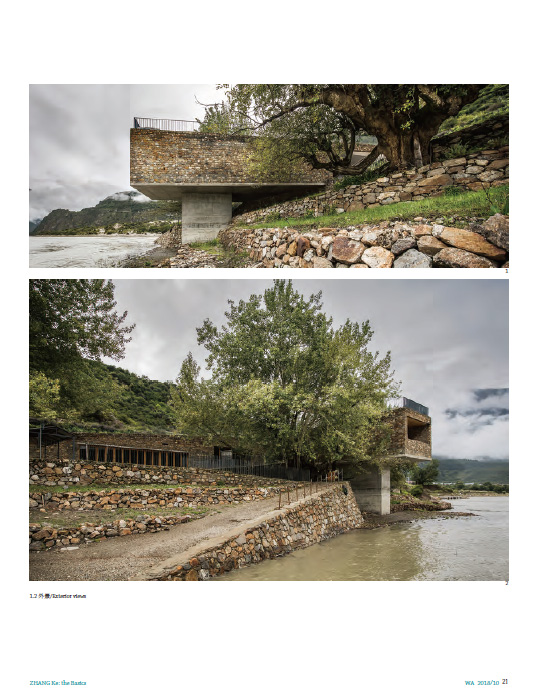

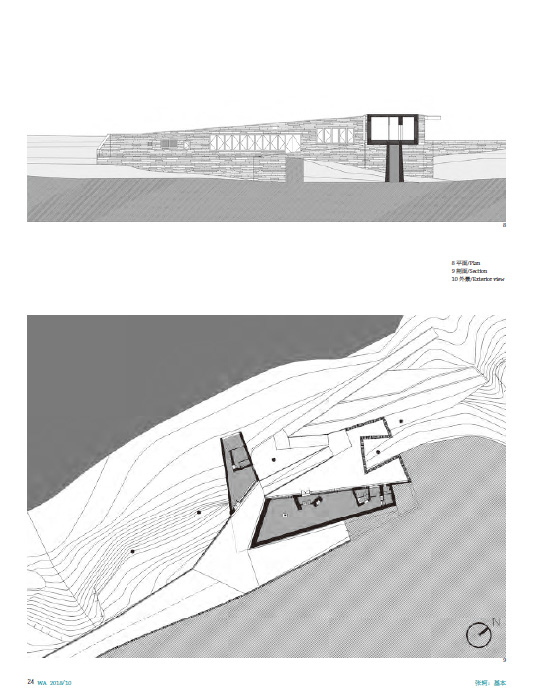

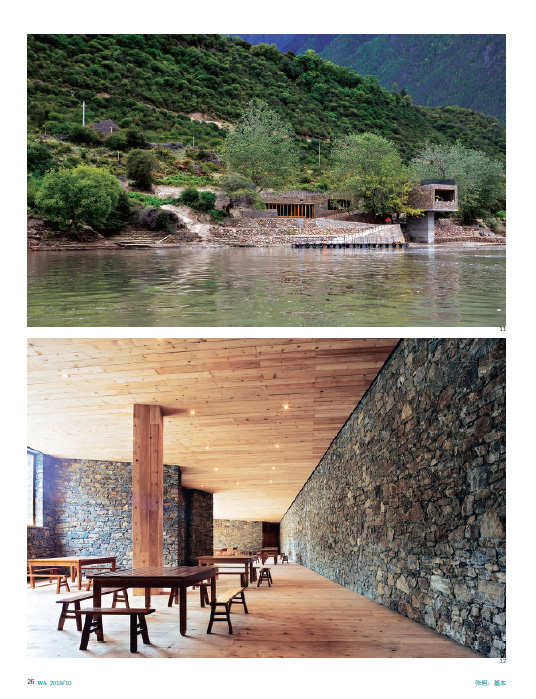

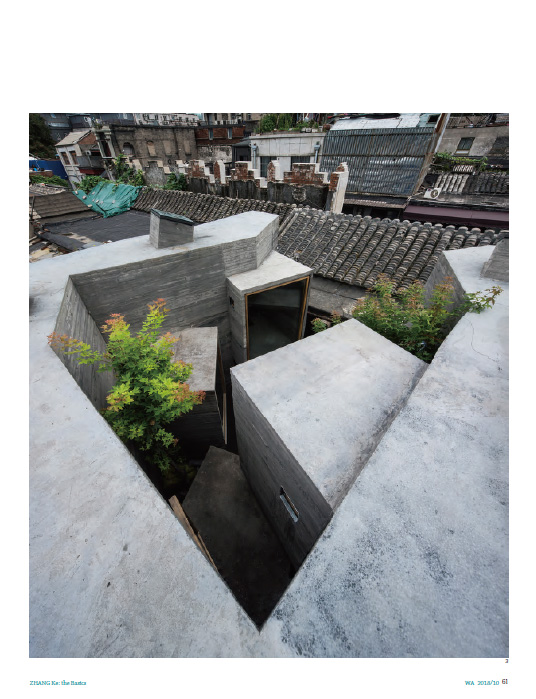

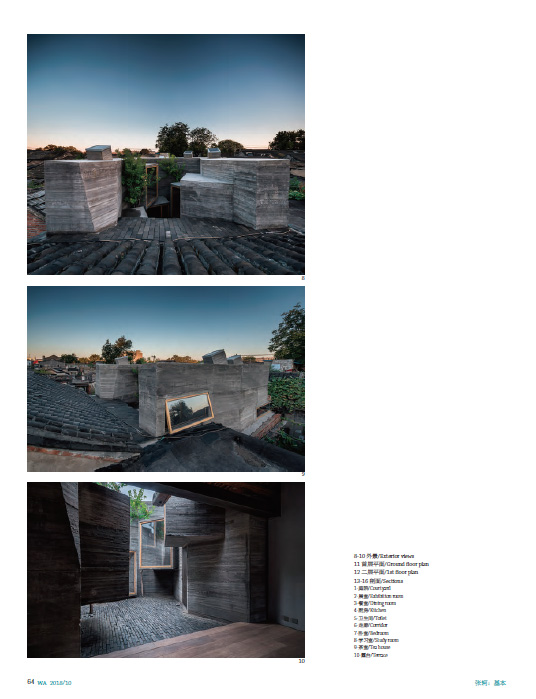

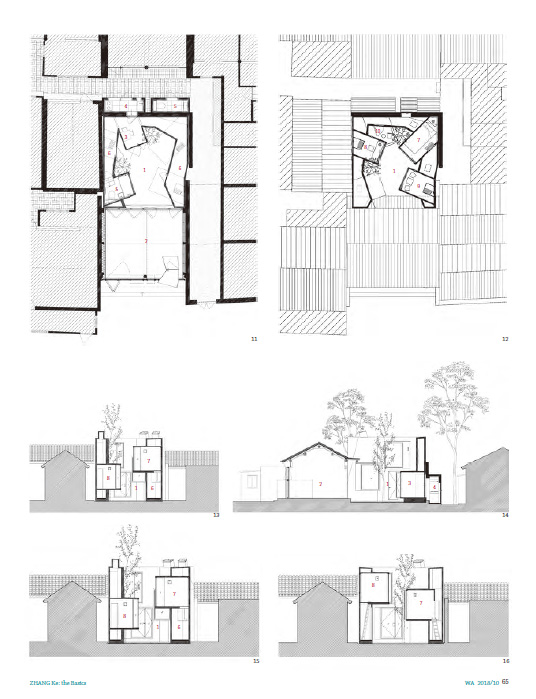

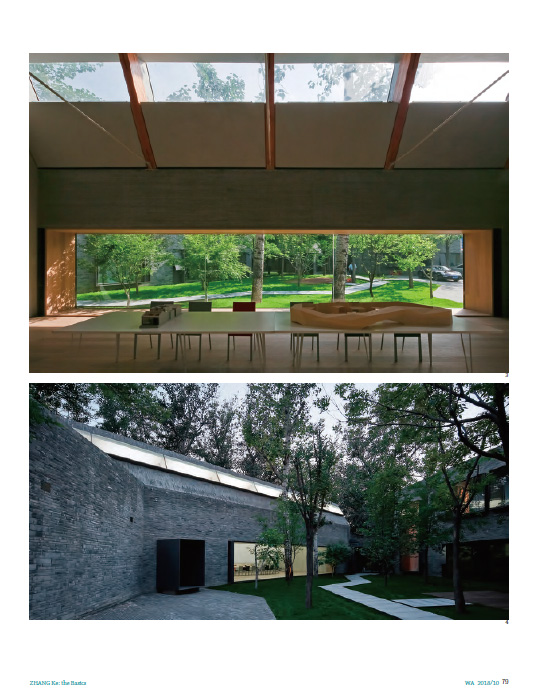

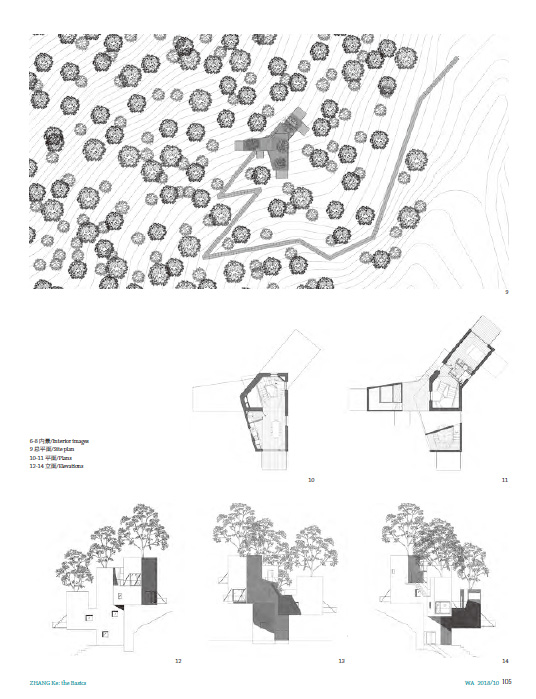

娘欧码头,林芝,西藏,中国

Niang'ou Boat Terminal, Linzhi, Tibet, China, 2013

建筑设计:标准营造+Embaixada

Architect: ZAO/standardarchitecture+Embaixada

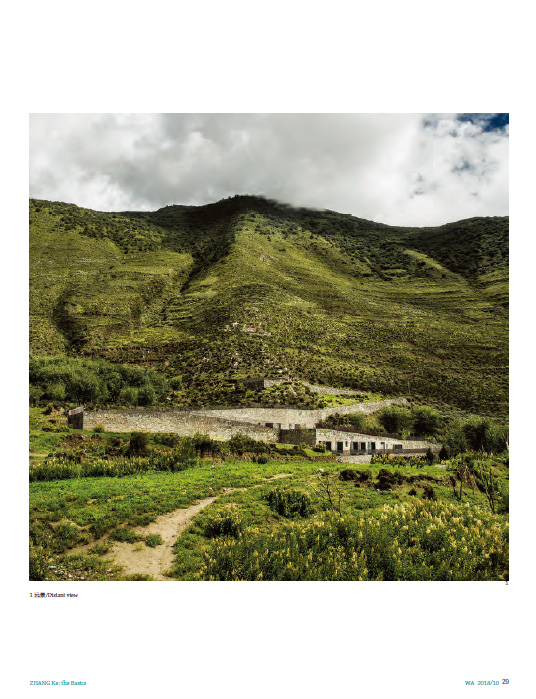

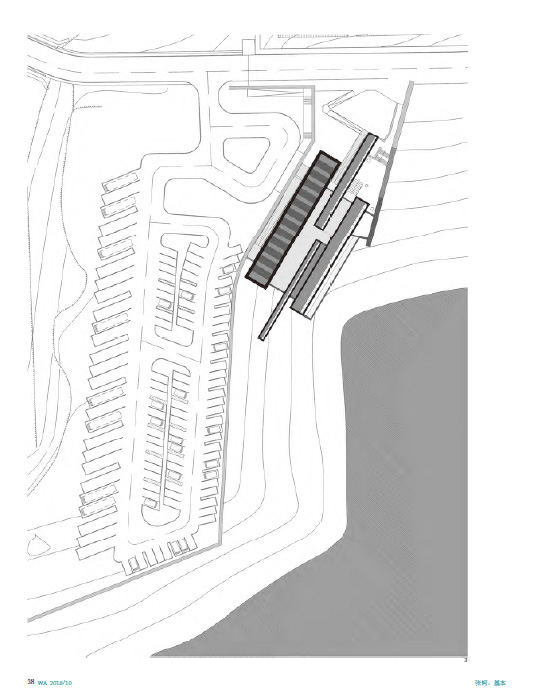

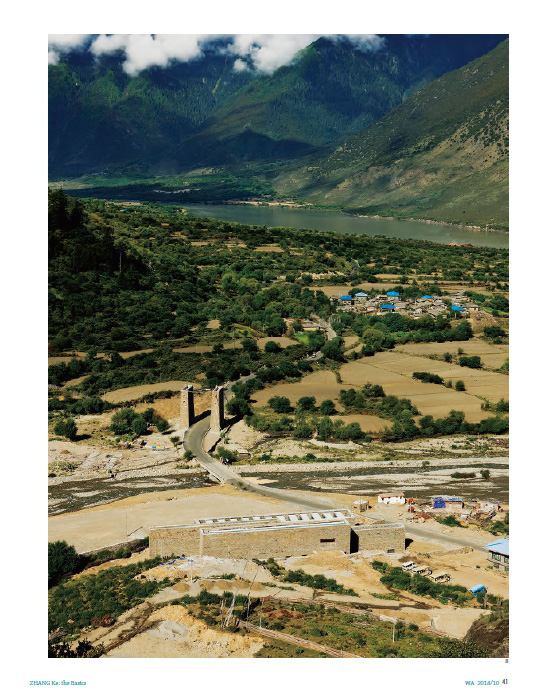

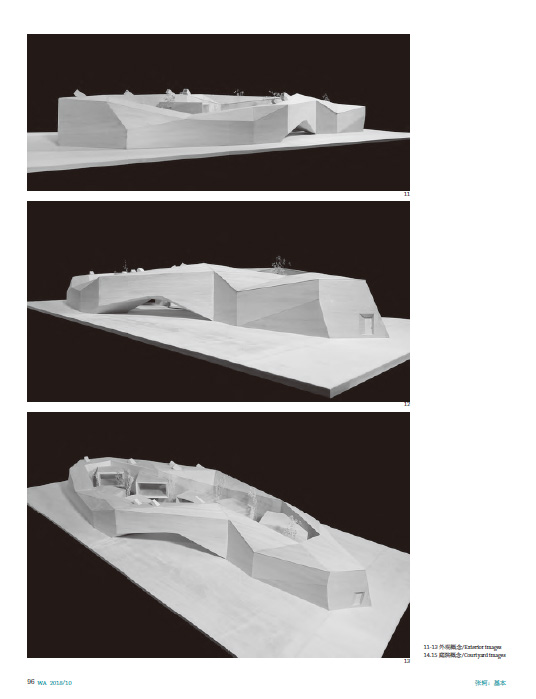

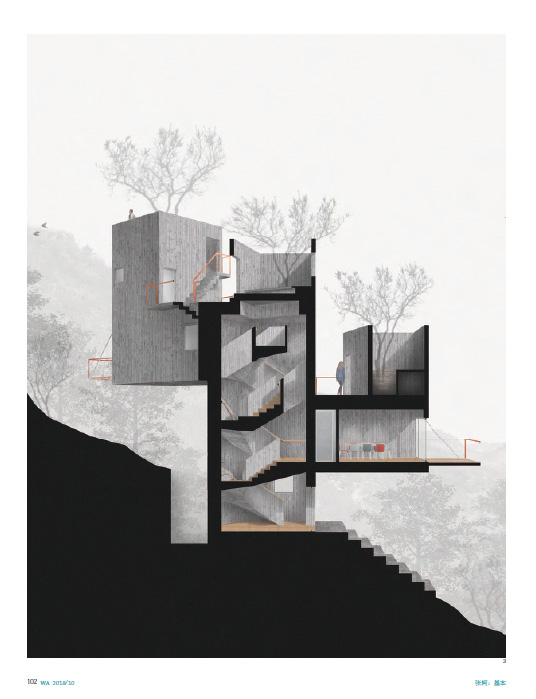

娘欧码头是继2008 年完工的派镇码头之后,标准营造与西藏旅游股份公司合作完成的一个较大的码头项目。这次标准营造邀请了好友葡萄牙年轻建筑师组合Embaixada 参加项目的前期设计。码头坐落在林芝县境内,尼洋河和雅鲁藏布江交汇口的娘欧村附近,雅鲁藏布江在此处形成了一个缓冲的自然港湾,岸边的沙洲上生长着树龄上百年的柳树林。再往上地势由舒缓逐渐转为陡峭,背后是绵延不断的无名雪山。

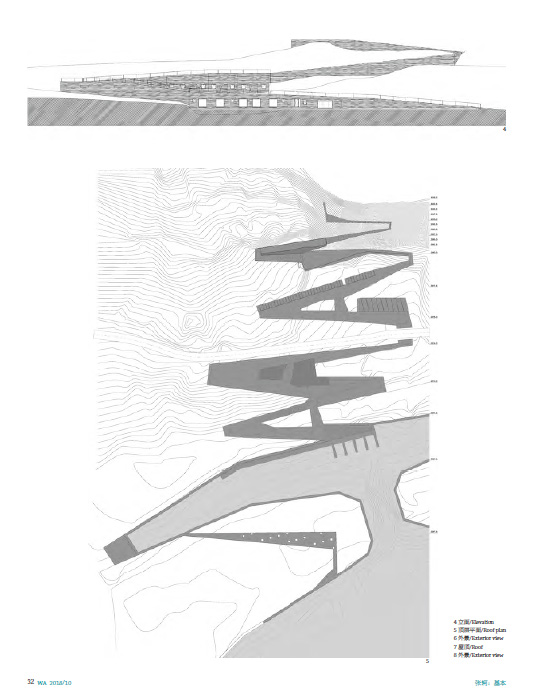

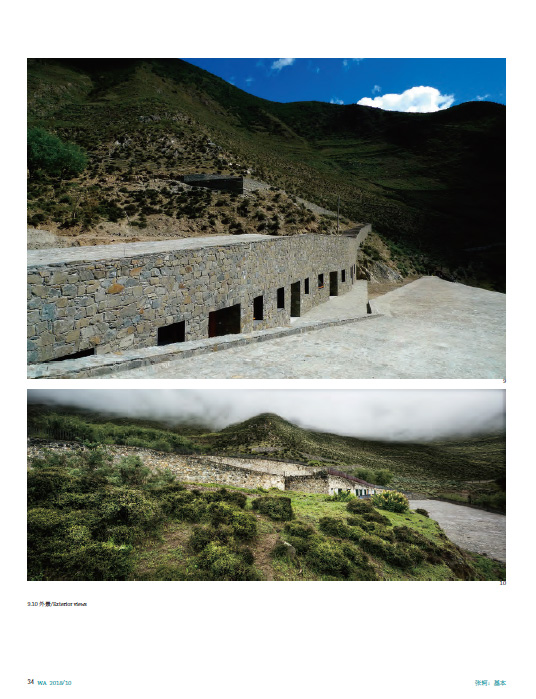

项目的概念源于对西藏人文建筑和自然景观的解读:在西藏,建筑与景观密不可分,建筑即是景观,景观即是建筑。娘欧码头的设计中,我们希望将建筑嵌于景观之中,它既不是景观的附属也不是脱离于景观之上,因此便有了这条迂回曲折的坡道,这条坡道把码头相对复杂的各种功能整合在一起。从公路往上,坡道组织了巴士停车场、船员宿舍、后勤办公、会议室和员工电影院等功能,直至海拔3000m,坡道成为一个观景平台,引导游客回望远处雅鲁藏布江与尼洋河汇合处的壮观景象。坡道从公路往下延伸,沉降至海拔2971m 的河岸,自然形成了驳船的码头,坡道下同样组织了售票厅、候船厅、餐厅、厨房、卫生间和发电站等多种服务与基础设施功能。这条坡道也因此定义了不同空间之间的复杂关系,生成了一个又一个平台和内部场所。建筑的每一块空间坚实地嵌入了周围的地势,协调着自然与人体间的微妙关系。

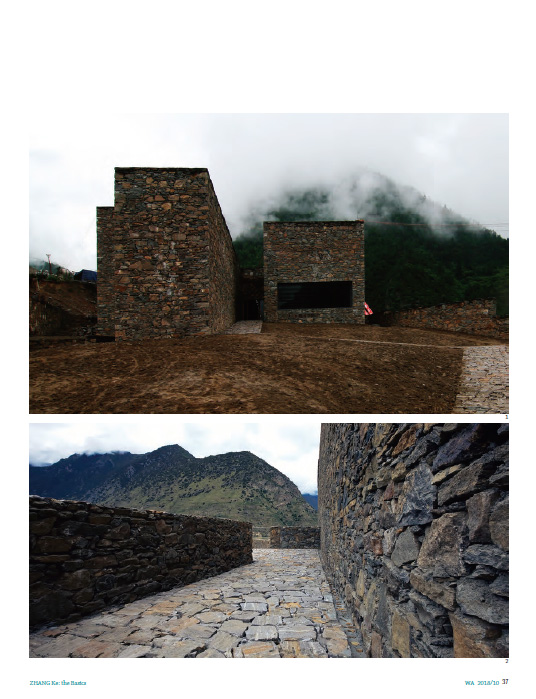

娘欧码头辗转迂回的体量不仅是对山势的诠释,也唤起了旅程的精神性。如同印度的下沉井在人步步下降的过程中辗转轮回,削弱了人与目的地的迫切联系,娘欧码头也试图延缓旅程。在向河岸的间接靠近中, 使人在脑海中积累了靠近水面的幻想,在最后一刻得到释放与满足。坡道辗转处形成一个个开阔平台。平台不仅仅是流线间的过渡,在运动之后的静止中的短暂思考,同时也为瞭望山野建立了一系列独特的视框。平台的边界清晰地定义了视野,突兀的山崖和荒乱的草木也为这个鲜明的视框增添了几分人文色彩。通过设置开阔平台,使人们在此驻足,平台引导着人的视线,唤起了山谷与河流自身的神性,使人心生敬畏。我们在探讨一个关于现象的问题:一片景观的本身也许原始冗余而自我重复,然而人们从某个特定角度对它的思考与凝视却能赋予它精神性。建筑所能做的,只是提供一个思考的角度,一个凝视的方向。

建筑在个别转折处,围拢成一个户外庭院。站在庭院里的人看到天空的切割,感受到对院外景色的神秘感与未知感。除此之外,这些的户外空间更是原始环境和人文环境之间的相互牵制、相互流通,让人曝露回归于山野自然间的同时给予人文的庇护。

像标准营造的其它西藏项目一样,娘欧码头的地域特征不是通过具象的装饰或形式来表达,而是通过本地特有的建筑与土地山川的一体关系,以及本地材料的创造性再运用得到演绎。娘欧码头的主体为混凝土框架结构加石头墙砌体完成,墙体的石头是从基地附近采集,由当地的石匠通过自己的砌造方式构成的,观景平台的栏杆以当地拾来的木柴充当,经过风吹日晒,一种西藏特有的质朴的精神性和隐秘的当代性悄然呈现。

Located in Linzhi County, Tibet, where Niyang River and the Yalung Zangbo River merge, the Niang'ou Terminal sits above a gently sloping bay, with old willows bowing over sand deltas. The bay then gradually turns into a steeper hill. Tiers of soft, nameless mountains stand behind.

The project originates from a reading of the primal landscape: in Tibet, architecture cannot be separated from landscape. The two are equivalent. In our design we immerse the building into the landscape, neither as an attachment or a detachment. Hence we arrive at this zigzagging path, which linearly integrates all complex functions. Arising from the highway, the ramp organizes parking, staff dormitories, offices, conference rooms and theater, forming a wide platform at 3000m by altitude, guiding one's eyes back at the magnificent union of rivers. From the highway down to an altitude of 2971m, one finds a ticket office, bathrooms, waiting room, canteen and kitchen leading to a dock near the water. The ramp defines the relationship between various spaces, creating a chain of platforms and places. Each and every space firmly lodges into the landscape, subtly mediating the human body with nature.

The twist and turns not only emphasises the mountain ridges, but also calls for the spirituality of the journey. In the same way that the turn-and-descend of an Indian step well complicates one's expectation of his destination, Niang'ou Terminal also stretches the course. When approaching to the river bank, one cannot help but imagining and envisioning until a release at the final moment.

Every twist forms a platform, serving not only as the transition between circulations, but also a pause for contemplation and a frame for outside views. The boundaries of platforms clearly defines a view frame, in which the barren hills and disheveled bushes take on a hint of humanity. We have discussing a problem of phenomenology here: a primal and redundant landscape becomes sacred, when gazed and pondered upon by human eyes. The building provides an angle for pondering, as well as a direction for gazing.

Like other projects in Tibet by ZAO/standardarchitecture, the regional character is not manifested through specific symbolisms, but through a unique relationship with mountains and rivers as well as the creative interpretation of local lumber. The main body of the terminal consists of a concrete frame, filled in by local masonry, stones gathered from near the site and patterned by local builders in their own technique. The railing is built from fire wood collected nearby, narrating, after exposure to weathers, a quiet and humble contemporaneity.

项目信息/Credits and Data

业主/Cl ient: 西藏旅游股份有限公司/Tibet Tourism Holdings

建筑设计/Archi tec t: 标准营造 + Embaixada/ZAO/standardarchitecture + Embaixada

设计团队/Design Team: 张轲,侯正华,张弘,陈玲,Claudia Taborda,Embaixada (Cristina Mendonca, Augusto Marcelino),孙青峰,戴海飞,盖旭东/ZHANG Ke, HOU Zhenghua, ZHANG Hong, CHEN Ling, Claudia Taborda, Embaixada (Cristina Mendonca, Augusto Marcelino), SUN Qingfeng, DAI Haifei, GAI Xudong

合作设计/Collaborate Design Institution: 中国建研建筑设计研究院,西藏有道建筑设计公司/China Academy of Building Research Architectural Design Institute, Tibet Youdao Architecture Associates

基地面积/Site Area: 35,000㎡

建筑面积/Building Area: 3300㎡

设计时间/Design Period: 2007-2013

摄影/Photos: 王子凌/WANG Ziling

评论

青锋:禁欲者的救赎

虽然有着藏式传统民居的厚重性,娘欧码头看起来却更为原始。几乎没有什么线索能够提示这个建筑的建造时代。它更像是某种原始宗教建筑的遗址,只是被今天的人们借用来作为旅游服务设施。这种联想显然受到了建筑形体的启发。在石板铺砌的屋顶上折返前行,会让人想起藏人虔诚的转山。没有佛像或者殿宇,行程本身成为信仰的明证。

为了营造这种氛围,建筑做出了不少常规意义上的牺牲。可以使用的内部空间仅仅占据整个项目的一小部分,一些房间的光线与景观也让位于建筑整体的紧凑连贯。建筑师自己的克制也是显而易见的,除了石砌墙体、门窗洞口、以及局部的木材堆叠的栏板之外,设计者放弃了其他能够呈现自己精湛技巧的机会。无论是在对待建筑师还是对待使用者上,标准营造的这个项目都展现出一种近乎于“禁欲”或者“苦行”的意味。

这种“禁欲”式的克制是标准营造近期作品的普遍特点。建筑师的语汇日益收敛,多余的东西都被屏蔽在外,设计最终归结于一两个要素。但也就是这一两个要素,所产生的触动却让人难以忘怀。不同于极少主义的做作,标准营造的这些作品追求的并不是空寂,而是在滤除了干扰的情况下,让某些要素更为凸显出来。这种要素,在近期作品中更多呈现为一种特殊的视景。就像标准营造所撰写的作品说明中所提到的,娘欧码头并不提供一个崇拜对象,它启示的是超越日常的审视。

这样的“禁欲”更接近于亚瑟·叔本华所阐述的“美学意识”,它需要我们摆脱“日常意识”对个体、对个人意志、对利益得失的过度关注,在非功利性的审视中超越个体性的悲剧。我们实际上可以把藏人的转山视为类似的解脱过程。娘欧码头的“宗教性”或者说是“哲学意味”并不仅仅限定在藏族传统中,在更广泛的意义上,它可以启示每一个人,无论他是否是佛教徒。

因为与日常生活的距离,阿道夫·路斯认为只有缺乏功能的艺术品才能具有这种“禁欲”的特征。在他看来只有这样的艺术品才能称为建筑,其他的都只是房屋。这种割裂显然过于绝对了,生活与启示并不一定要相互对立,在娘欧码头的石台之上,或许可以感受到两者之间内在的联系。

Comment

QING Feng: The Redemption of Ascetics

Although bearing the heaviness of Tibetan traditional residence, the Niang'ou Boat Terminal looks even more primitive. There is hardly any clue indicating the construction time of the building. It's more like relics of some primitive religious architecture, only borrowed by people today as a tourist service establishment. This association is obviously inspired by the architectural formation. Walking back and forth on the stone paved roof reminds people of the Tibetan's pious mountain circling. Without any sacred statues or temples, the journey itself becomes a clear proof of faith.

In order to create such an atmosphere, the architecture had to sacrifice a lot in the conventional sense. Not only does the accessible interior space occupy merely a small part of the whole project, but the light and sight of some rooms also give way to the compactness and coherence of the whole building. The architect's own restraint is also evident. Apart from the stone masonry walls, the openings of doors and windows, and the stacked timber fences here and there, the designer abandoned any other opportunities to present his virtuosity. Whether for the architect or the users, this project of ZAO shows a sense that almost reaches the level of "abstinence" or "asceticism".

This "ascetic" restraint is the common characteristics of ZAO's recent works. The architect's vocabulary is increasingly constricted, redundant things are warded off, and design ultimately concentrates into only one or two elements. But precisely these one or two elements could cause an unforgettable stir. Different from the affectation of minimalism, what ZAO pursues is not emptiness, but letting certain elements stand out in the absence of any interference. Frequently, the distinctive elements chosen by ZAO falls into the category of special sights. As it is mentioned in the design description, Niang'ou Boat Terminal does not offer an object of worship, but inspires transcendent reflections.

Such "asceticism" is closer to the "aesthetic consciousness" described by Arthur Schopenhauer. It requires us to get rid of the excessive attention on the individual, the will, and the gain and loss in "ordinary consciousness", thus to overcome the individual tragedy by way of non-utilitarian contemplation. In fact, we can regard Tibetans' mountain circling as a similar process of liberation. The "religious" or "philosophical" meaning of Niang'ou Boat Terminal is not limited to the Tibetan tradition. In a broader sense, it can inspire everyone, whether Buddhist or not.

Because of the distance from everyday life, Adolf Loos believes that only works of art lacking function can possess this kind of "ascetic" characteristic. In his opinion, only such works of art could be called architecture, and others are just buildings. This split is obviously too absolute. Life and revelation do not necessarily oppose each other. On the stone platform of Niang'ou Boat Terminal, one may feel the internal connection between them. (Translated by CHEN Yuxiao)

南迦巴瓦接待站,林芝,西藏,中国

Tibet Namchabarwa Visitor Centre, Linzhi, Tibet, China, 2008

建筑设计:标准营造

Architect: ZAO/standardarchitecture

林芝南迦巴瓦接待站是标准营造继雅鲁藏布江小码头之后,在西藏建成的另一个房子。在西藏做建筑需要面对很多挑战,首要的问题是应该用怎样的态度来对待西藏文化?如何对待本地原有的、带有强烈色彩和装饰性的建筑传统?新建筑与周边原有建筑形成怎样的关系?如何处理建筑与基地、建筑与大范围地形及自然景观的关系?建造过程如何考虑当地工匠、当地技术的参与?在恶劣的气候和有限的资金条件下,哪些材料和建造方式是可行的,而哪些是不现实的?是否可以用一种平视和平等的态度对待西藏的文化?是否可以既不俯视又不仰视特有的西藏文化?在强调保护传统西藏文化的同时,当代西藏文化有没有发展空间?如果有,作为当代西藏文化重要组成部分的当代西藏建筑在哪里?

2007 年6 月,我们几个人带着所有这些的问题,辗转来到了西藏林芝地区雅鲁藏布大峡谷中的南迦巴瓦雪山脚下,开始了雅鲁藏布江沿线从林芝机场到雪山脚下的直白村约80km 的公路、水路交通设施的规划设计踏勘工作。并没有详细任务书,也没有建筑选址,只知道要为雅鲁藏布大峡谷和南迦巴瓦雪山景区建造一个游客接待站。在精疲力竭地走了3 天的江边徒步转经线之后,终于在地图上确定了接待站的详细位置。

接待站位于藏东南林芝地区米林县境内的一个小集镇,名叫派镇,小镇海拔约2900m,东面是海拔7782m 的南迦巴瓦雪山和加拉白垒雪山,北面紧邻雅鲁藏布江,南面是多雄拉雪山,镇的主街正对着由多雄拉雪山延伸下来的高坡。小镇的前身是经过雅鲁藏布江往全国唯一不通公路的墨脱县运送物资的转运站,有一个简易码头和几十户人家,由于是水路和陆路交通的交汇点,近些年逐渐成为林芝地区一个旅游小集镇,这里不但是雅鲁藏布大峡谷的入口,也是重要的宗教转经线——“转加拉”的起点,还是通往墨脱徒步旅行的出发点。

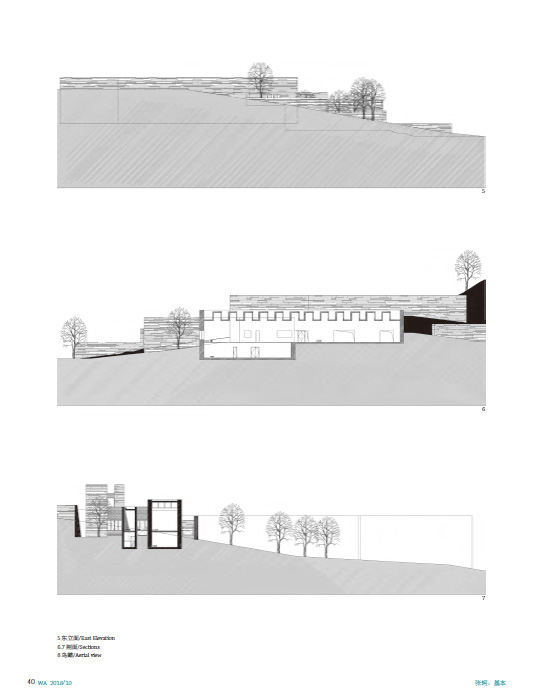

接待站就坐落在小镇入口的山坡上,面对着雅鲁藏布江和公路的方向,西面是一条由多雄拉雪山溶化流下来的溪流,再往西是农田和名叫“派村”的原始村落。接待站总面积约1500㎡,功能较为复杂,包括一个大峡谷综合信息展厅、一组公共厕所、徒步装备及食品小卖部、背包客的行李物品存放处、网吧、急救医务室、大峡谷景区的售票检票点、旅游公司办公室和司机导游休息室等等,同时还设置了一个为全镇服务的集中配电房。

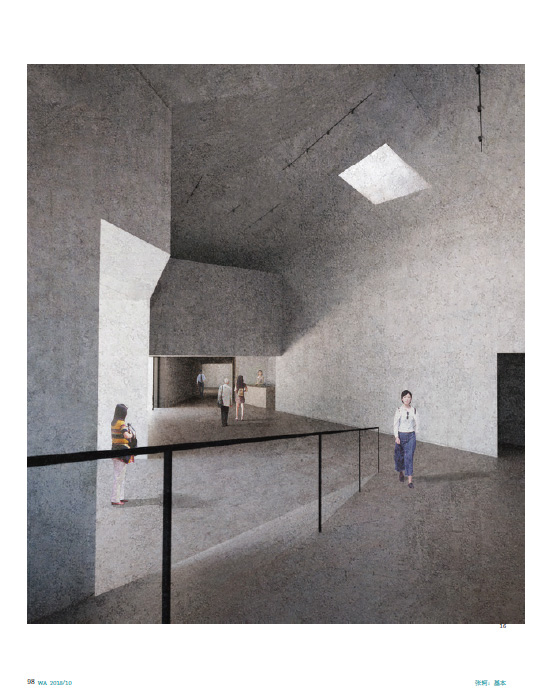

我们显然对本地建筑形式的模仿和拼凑不感兴趣,也显然对移植一个时尚的外来建筑不感兴趣。接待站是一个形式上很不显眼的建筑,远远看去,当地人甚至看不出它有什么新奇,它随行就势,由几个高低不一、厚薄不同的石头墙体从山坡不同高度随意地生长出来的体量构成,墙体内部是相应的功能空间,这样多数功能空间实际上是半掩藏在山坡下的。

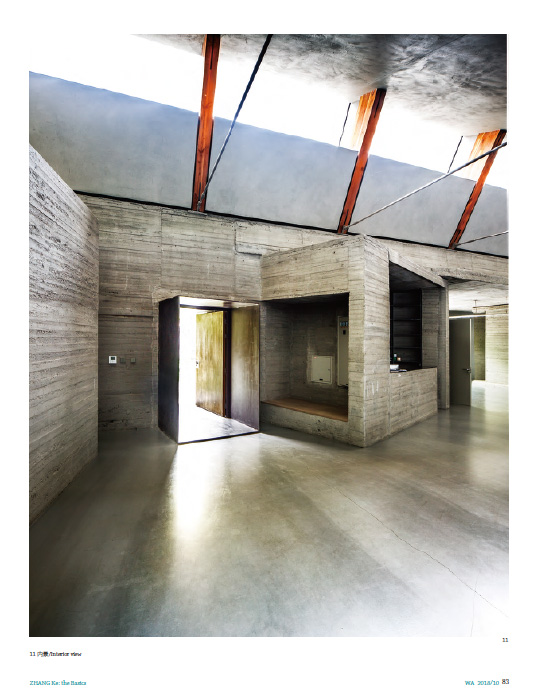

建筑随着基础的标高不同分为3 层,地下一层是储藏室和集中配电房;一层主要是各种接待空间,大峡谷信息展厅、厕所、医务室、网吧小卖部、景区售票检票都在这一层;二层是后勤办公室和可供游客休息观景的屋顶平台。建筑的采光主要通过两种天窗解决:为接待大厅采用屋顶凹陷形成的高侧窗,楼梯、网吧和办公室采用的是细长的天窗。整个建筑只在一层接待大厅朝向雅鲁藏布江及加拉白垒雪山的方向和二层办公室朝向南迦巴瓦雪山的方向开了两个明确的景观视窗。

建筑的结构体系是传统砌筑石墙和混凝土混合结构。墙体从60cm、80cm 到1m 厚不等,全部由当地石材砌筑而成。石头墙是自承重的,墙内附设构造柱、圈梁和门窗过梁,起到增强石墙整体性的抗震作用,同时用来支撑混凝土现浇的屋顶。砌筑石墙的藏族工匠主要是来自日喀则,他们在石墙的砌筑上有很特别的习惯和方法,这一点是我们在图纸上设计不出来的。

建筑的门窗和室内没有使用任何常见的“西藏形式”的门窗装饰,我们毫不回避南迦巴瓦接待站是一个当代建筑,如果人们可以感受到特殊的本地气质,我们希望这种气质是通过本地的材料以真实而朴素的建造过程自然形成的,而不是“乔装改扮”的结果。

The visitor centre is the second building designed by standardarchitecture in Tibet after the Yalung Zangbo Boat Terminal. It is located in a small village called Pai Town in Linzhi, southeastern part of Tibet Autonomous Region. The building sits on a slope along the road leading to the last village Zhibai deep in the Yalung Zangbo River Grand Canyon , facing the Yalung Zangbo River to its north and with the 7782-metre-high Mount Namchabarwa at its background in the east.

The 1500㎡ building serves as a visitor centre providing comprehensive information about Mount Namchabarwa and the Yalung Zangbo Grand Canyon. It serves also as the "town centre" for the villagers as well as the supply base for the backpack hikers exploring the canyon. Therefore the programme is quite complicated. It includes a reception/information hall, public toilets, a supply store, an internet bar, a medical centre, locker room for backpackers, meeting rooms, offices for tour guides and drivers, a water reservation tank and a central electrical switch house for the village.

Like a few slices of rock extending out of the mountains, the building is conceived as a series of stone walls merging into the slope, with no windows facing the incoming road in the west, almost scale-less, an abstract landscape in the natural landscape. Looking from afar it neither hides itself, nor stands out from its background as a piece of "Tibetan" architecture.

Approaching from a distance on the road, people cannot be sure if this is a building or a set of retaining wall or even a "Mani" wall at the foot of the mountain. After getting out of cars, visitors will follow a pathway led by a stone retaining wall up the hill, where they find the main entrance to the reception/exhibition hall. The main hall is lit by sky lights and has a view window facing north towards the village and the Yalung Zangbo River. Entering the second layer of the 1-metre-thick stone wall, visitors find the public toilets and the public luggage storage room, going further through another layer of stone wall they find the internet café, medical clinic and a rest area for drivers. Halfway they have the choice of taking the "stair way to heaven" up to the second floor for the roof garden and the meeting rooms. The water tank is hidden beneath the stairs and the electric switch room takes the underground space.

After a brief rest, gathering necessary information of the area and other supplies, sending out emails to friends and relatives, visitors are again led by a zigzagged stone path way down the hill into the village, and the start to explore the Mount Namchabarwa, disappearing into the no-man-forest of the Yalung Zangbo valley for days and weeks.

项目信息/Credits and Data

建筑设计/Architect: 标准营造/ZAO/standardarchitecture

设计团队/Design Team: 张轲,张弘,侯正华,Claudia Taborda,Maria Pais de Sousa,盖旭东,孙伟,杨欣荣,王风,刘新杰,孙青峰,黄狄,陈玲/ZHANG Ke, ZHANG Hong, HOU Zhenghua, Claudia Taborda, Maria Pais de Sousa, GAI Xudong, SUN Wei, YANG Xinrong, WANG Feng, LIU Xinjie, SUN Qinfeng, HUANG Di, CHEN Ling

合作设计/Collaborate Design Institution: 中国建研建筑设计研究院,西藏有道建筑设计公司/China Academy of Building Research Architectural Design Institute, Tibet Youdao Architecture Associates

结构形式/Structural System: Mixed - Stone Masonry and Concrete Reinforcement, Concrete Roof

项目功能/Programme: 游客接待站/Visitor Centre

基地面积/Site Area: 10,000㎡

建筑面积/Building Area: 1500㎡

设计时间/Design Period: 2007

施工时间/Construction Period: 2007-2008

摄影/Photos: 陈溯/CHEN Su

评论

赵扬:这个建筑的用意似乎更倾向于和周边自然景观的对话,而不是从内部功能和内部空间体验出发。建筑的表情是抽象而极简的。因为将建筑体量都归纳成长短宽窄不同的长方体,而且统一使用当地比较常见的毛石来覆盖或砌筑,整个建筑的立面也尽可能减少了门窗开洞可能附加的表情(主要的室内空间都采用天光照明)。唯一被建筑师强调的“建筑手段”是这些毛石体量在平面进退、立面高低上错落安排出的有机形态。而这一形态却没有被僵化成一个或若干个固定的构图,也没有暗示任何确定的观察角度,似乎是在回避任何可能的概念性或形式化的解读。也许建筑师最大的用心处和着力点就是在于这“回避”二字。

回避了所有可能的概念性解读,也许我们会忘记这个房子的时代,我们的感受开始和那些古老而原始的人类经验相接。我们体会到一种类似“纪念性”的东西。这种纪念没有具体的对象和所指,是一种比较“无心”的庄严。让我想起阿道夫·路斯那段著名的话:“如果我们在树林里碰到一个土堆,六英尺长,三英尺宽,用泥土堆成的一个金字塔形,我们心中升起一种肃穆的情绪,它会告诉我们‘有人葬于此地’。这是建筑。”

Comment

ZHAO Yang: The intention of this building seems to be more about the conversation with the surrounding natural landscape than starting from the internal functions and experience of the interior space. The expression of the building is abstract and minimalist by nature, because the volume of the building is categorised into cuboids of different sizes, the building is uniformly covered or built with ashlar, which is common in the local area, and the openings of doors and windows are also minimized all over on the facades to reduce the possibility of additional expression (main parts of the indoor space are illuminated by skylight). The only "architecture measure" emphasised by the architect is the organic form arranged through the horizontal and vertical shuffling of the ashlar. But this form is not rigidified into one or more fixed compositions, nor does it imply any definite perspective of observation, as if to be avoiding any possible conceptual or formal interpretation. Perhaps the architect's greatest concern and focus is the word "avoidance".

Avoiding all the possible conceptual interpretations, we may forget the time of this building, and our feelings begin to connect with those ancient and primitive human experiences. We experience something similar to "commemoration". This kind of commemoration has no specific object or reference. It's a relatively "unintentional" solemnity. It reminds me of Adolf Loos's famous words: "If we were to come across a mound in the woods, six foot long by three foot wide, with the soil piled up in a pyramid, a somber mood would come over us and a voice inside

us would say, 'There is someone buried here.' That is architecture."(Translated by CHEN Yuxiao)

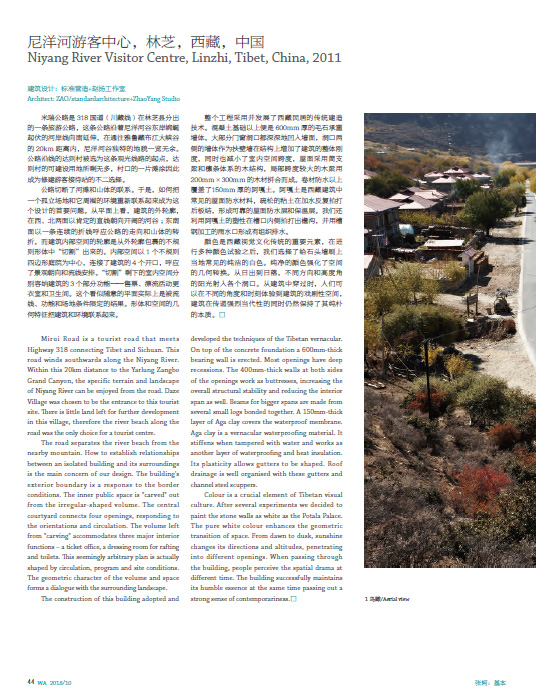

尼洋河游客中心,林芝,西藏,中国

Niyang River Visitor Centre, Linzhi, Tibet, China, 2011

建筑设计:标准营造+赵扬工作室

Architect: ZAO/standardarchitecture+ZhaoYang Studio

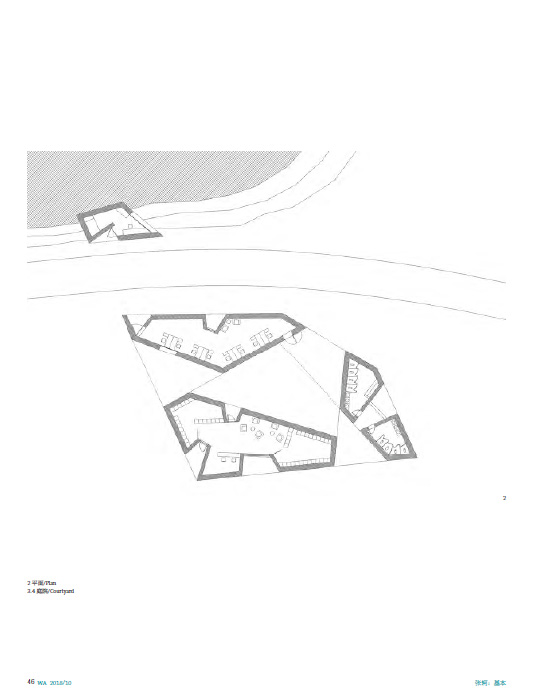

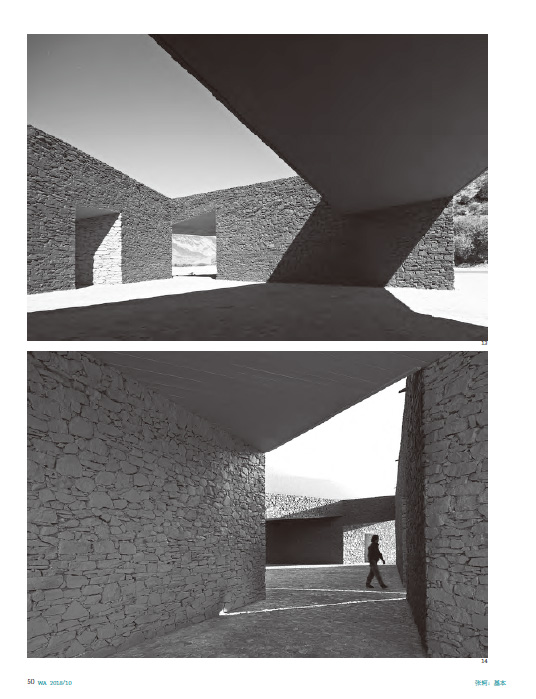

米瑞公路是318 国道(川藏线)在林芝县分出的一条旅游公路,这条公路沿着尼洋河谷东岸婉蜒起伏的河岸线向南延伸,在通往雅鲁藏布江大峡谷的20km 距离内,尼洋河谷独特的地貌一览无余。公路沿线的达则村被选为这条观光线路的起点,达则村的可建设用地所剩无多,村口的一片滩涂因此成为修建游客接待站的不二选择。

公路切断了河滩和山体的联系。于是,如何把一个孤立场地和它周围的环境重新联系起来成为这个设计的首要问题。从平面上看,建筑的外轮廓,在西、北两面以肯定的直线朝向开阔的河谷;东南面以一条连续的折线呼应公路的走向和山体的转折。而建筑内部空间的轮廓是从外轮廓包裹的不规则形体中“切割”出来的。内部空间以1 个不规则四边形庭院为中心,连接了建筑的4 个开口,呼应了景观朝向和流线安排。“切割”剩下的室内空间分别容纳建筑的3 个部分功能——售票、漂流活动更衣室和卫生间。这个看似随意的平面实际上是被流线、功能和场地条件限定的结果。形体和空间的几何特征把建筑和环境联系起来。

整个工程采用并发展了西藏民居的传统建造技术。混凝土基础以上便是600mm 厚的毛石承重墙体。大部分门窗洞口都深深地凹入墙面,洞口两侧的墙体作为扶壁墙在结构上增加了建筑的整体刚度,同时也减小了室内空间跨度,屋面采用简支梁和檩条体系的木结构,局部跨度较大的木梁用200mm×300mm 的木材拼合而成。卷材防水以上覆盖了150mm 厚的阿嘎土。阿嘎土是西藏建筑中常见的屋面防水材料,疏松的粘土在加水反复拍打后板结,形成可靠的屋面防水层和保温层。我们还利用阿嘎土的塑性在槽口内侧拍打出檐沟,并用槽钢加工的雨水口形成有组织排水。

颜色是西藏视觉文化传统的重要元素,在进行多种颜色试验之后,我们选择了给石头墙刷上当地常见的纯洁的白色。纯净的颜色强化了空间的几何转换。从日出到日落,不同方向和高度角的阳光射入各个洞口。从建筑中穿过时,人们可以在不同的角度和时刻体验到建筑的戏剧性空间,建筑在传递强烈当代性的同时仍然保持了其纯朴的本质。

Mirui Road is a tourist road that meets Highway 318 connecting Tibet and Sichuan. This road winds southwards along the Niyang River. Within this 20km distance to the Yarlung Zangbo Grand Canyon, the specific terrain and landscape of Niyang River can be enjoyed from the road. Daze Village was chosen to be the entrance to this tourist site. There is little land left for further development in this village, therefore the river beach along the road was the only choice for a tourist centre.

The road separates the river beach from the nearby mountain. How to establish relationships between an isolated building and its surroundings is the main concern of our design. The building's exterior boundary is a response to the border conditions. The inner public space is "carved" out from the irregular-shaped volume. The central courtyard connects four openings, responding to the orientations and circulation. The volume left from "carving" accommodates three major interior functions – a ticket office, a dressing room for rafting and toilets. This seemingly arbitrary plan is actually shaped by circulation, program and site conditions. The geometric character of the volume and space forms a dialogue with the surrounding landscape.

The construction of this building adopted and developed the techniques of the Tibetan vernacular. On top of the concrete foundation a 600mm-thick bearing wall is erected. Most openings have deep recessions. The 400mm-thick walls at both sides of the openings work as buttresses, increasing the overall structural stability and reducing the interior span as well. Beams for bigger spans are made from several small logs bonded together. A 150mm-thick layer of Aga clay covers the waterproof membrane. Aga clay is a vernacular waterproofing material. It stiffens when tampered with water and works as another layer of waterproofing and heat insulation. Its plasticity allows gutters to be shaped. Roof drainage is well organised with these gutters and channel steel scuppers.

Colour is a crucial element of Tibetan visual culture. After several experiments we decided to paint the stone walls as white as the Potala Palace. The pure white colour enhances the geometric transition of space. From dawn to dusk, sunshine changes its directions and altitudes, penetrating into different openings. When passing through the building, people perceive the spatial drama at different time. The building successfully maintains its humble essence at the same time passing out a strong sense of contemporariness.

项目信息/Credits and Data

业主/Cl ient: 西藏旅游股份有限公司/Tibet Tourism Holdings

建筑设计/Architect: 标准营造+赵扬工作室/ZAO/standardarchitecture+ZhaoYang Studio

设计团队/Design Team: 张轲,张弘,侯正华,赵扬,陈玲/ZHANG Ke, ZHANG Hong, HOU Zhenghua, ZHAO Yang, CHEN Ling

工地技术员/Contractor: 胡启良/HU Qiliang

结构形式/Structural System: 毛石承重墙+简支木结构屋面/Stone load-bearing wall + timber roof

工程造价/Cost: RMB 1,000,000

建筑面积/Building Area: 430㎡

设计时间/Design Period: 2009.01-2009.05

施工时间/Construction Period: 2009.06-2011.06

摄影/Photos: 陈溯/CHEN Su(fig.1,13,14),标准营造/ZAO/standardarchitecture(fig.3,4,11,12)

评论

张宇星:建筑师内心深处的最大抵抗,是对建筑非纯粹性的抵抗。这种非纯粹性来自于各个方面:可能是每天轰炸视觉神经的全球图像污染,也可能是被某种话语体系赋予了权威力量的审美定式,或者,是一些似是而非的文化概念(比如所谓地域性、历史文脉等)。面对这些纷至冗来和纷繁复杂的世界幻像,建筑师就像是一个远古巫师,他需要以删繁就简的最大勇气来唤醒建筑(和土地)中隐藏的空间神性,就像是唤醒一颗草籽,从地表深处破土而出,然后演变成为一个“自生长空间构形”。某种意义上,好的建筑应该是具有“植物性”和“动物性”的。尼洋河游客中心就是这样一个可以称之为“自然结晶物”的原型空间,建筑师张轲所做的其实很简单,就是“在一团虚无缥缈中,把多余的空气去掉,剩下的就是建筑”。

当然,在这个自然结晶过程中,最重要的手法是需要对空间进行不断提纯,同时赋予空间内在多重张力,使之获得语言逻辑和语言形式的极端抽象感。这种极端抽象感在本质上是感性(和性感)的,因为它投射了空间最深层次的生物学本性。

应当说,尼洋河游客中心的“空间提纯实验”是非常成功的,它主要在6 个方面探索了空间的张力平衡技巧。(1)重和轻:用非常重的石材来反向表达轻盈和悬浮,或者用非常轻盈的手法来切割石头重块,这种矛盾性消解了材料和结构的文化地域符号特质,突出了对地球重力“控制与反控制”的自由精神属性;(2)光和暗:不规则的几何形转折系统消解了人对光线轨迹的定位感知,于是光和暗不再具有规规矩矩的太阳方位属性,而产生了一种奇妙的捉迷藏似的“游戏神性”;(3)实和空:实体内部“整体包裹”了外部虚空(院落和室外开放空间),同样,在虚空中也可以体会到实体被虚空“整体分离”的冲突性力量;(4)内和外:建筑的内部不仅仅是“物理性的内部”,而是“身体性的内部”以及“心理性的内部”,只有把内部压缩得具有足够的“紧密感”和“内视感”,外部才能获得无限的延展性扩张力;(5)景和观:如果说“景”是一种不加预设的由使用者自我定义的观看系统,那么“观”则是由建筑师精心预设的“内心景观”观看系统。所以“观”是与一些特定设计的“窗口”(洞口、缝隙)相关联的,我们可以在尼洋河游客中心以及张轲后期设计的大量案例中,发现这种“观景窗口原型”;(6)游和览:具有不确定性特征的动线设计常常会让观赏者感受神秘探幽的乐趣,但过于隐秘的空间逻辑也会使建筑变得玄妙难懂,因此布置一些总览全局的“全景阅读场景”(可能是制高点或者全景视点)变得尤为必要,它将成为整个游览过程的真正高潮。

总之,尼洋河游客中心通过对重和轻、光和暗、实和空、内和外、景和观、游和览这一系列巧妙的张力平衡设计,使建筑从“地域性的概念化桎梏”中跳了出来,回归到空间本原,让我们领悟到源于地点又高于地点的空间神性。也许可以说,这种空间本原和空间神性才是具有打动人灵魂力量的真正地域性。

Comment

ZHANG Yuxing: The greatest resistance of architects is that against the non-purity of architecture. This kind of non-purity comes from various aspects: it may be the global image pollution that bombs the visual nerves every day, it may be an aesthetic stereotype that is endowed with authority by a certain discourse system, or, it may be some specious cultural concepts (such as the so-called regional, historical context, etc.). In the face of these redundant and complex phantoms of the world, the architect is like an ancient wizard who needs the greatest courage of condensation to awaken the hidden divinity of space hidden in architecture (and land), like awakening a grass seed to break through surface of the earth from deep in, and then evolves into a "self-growing space structural form". In a sense, good architectures should be "vegetative" and "animalistic". The Niyang River Visitor Centre is such a prototype space that can be called a "natural crystals". What the architect ZHANG Ke does is simple: "In a mass of vanity, remove the excess air, and the rest is architecture." Of course, in this natural crystallisation process, the most important method is to constantly purify the space and give the space inherent multiple tensions in the meantime, so that it can obtain the extreme abstraction of language logic and language form. This extreme abstraction is essentially perceptual (and sexy), because it projects the deepest biological nature of space.

It's safe to say that the "space purification experiment" of Niyang River Visitor Centre is very successful. It mainly explored the tension balance techniques of space in six aspects. (1) Heaviness and lightness: conversely expressing lightness and levitation with very heavy stones, or cutting heavy stone blocks with very light techniques, this contradiction dispels the cultural and regional symbolic characteristics of materials and structures, and highlights the spiritual attributes of freedom in the "control and anti-control" of the earth's gravity; (2) Light and shadow: the irregular geometric turning system eliminates people's location perception of light trails, so that light and darkness no longer have the regular properties of solar orientation, resulting in an intriguing "game divinity" like hide-and-seek; (3) Solidity and emptiness: the inner solid "wholly enwraps" the outer void (courtyard and outdoor open space),similarly, the conflicting forces of the solid being "wholly separated" by the void can also be experienced in the void; (4) Inside and outside: the inside of the building is not only "physical inside", but also "bodily inside" and "psychological inside", only by compressing the inside until it have enough "compact" and "insight" can the outside obtain infinite ductility and extensibility; (5) Scene and view: if the "scene" is a kind of unexpected user-defined viewing system, then the "view" is a "mind landscape" viewing system elaborately designed by the architect. So the "view" is associated with certain specially designed "windows" (openings, gaps), and we can find this "viewing window prototype" in the Niyang River Visitor Centre and a large number of later cases designed by ZHANG Ke; (6) Tour and Visit: the route design with uncertain characteristics often makes the viewer feel the fun of exploring mysteries, but spatial logic too secretive can also make the building abstruse and difficult to understand, so the setting of some "panoramic reading scenes" (may be high spots or panoramic viewing spots) that look onto the overall becomes particularly necessary as the real climax of the entire touring process.

In short, through a series of ingenious tension balancing designs of heaviness and lightness, light and darkness, solidity and emptiness, inside and outside, scene and view, tour and visit, the design of Niyang River Visitor Centre makes the building jump out from the "conceptual shackles of regionalism" and return to the space itself, so that we can feel the spatial divinity coming from the place but higher than the place. Perhaps it can be said that this kind of spatial primitive and spatial divinity is real regionalism with the power to speak to people's souls. (Tranlated by CHEN Yuxiao)

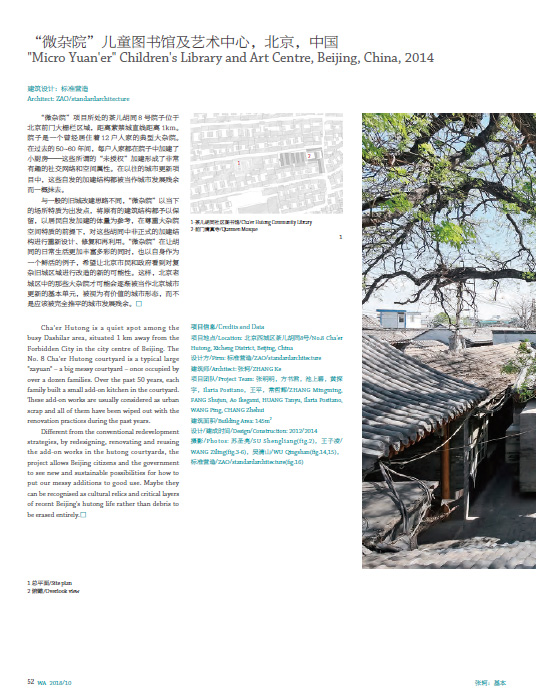

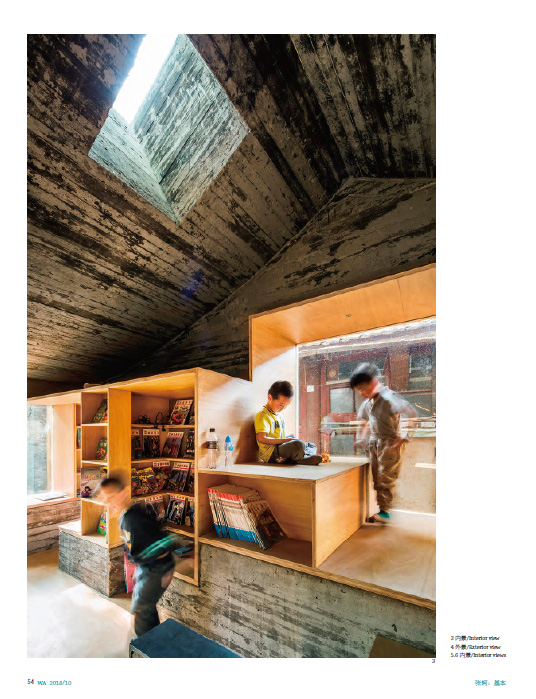

“微杂院”儿童图书馆及艺术中心,北京,中国

"Micro Yuan'er" Children's Library and Art Centre, Beijing, China, 2014

建筑设计:标准营造

Architect: ZAO/standardarchitecture

“微杂院”项目所处的茶儿胡同8 号院子位于北京前门大栅栏区域,距离紫禁城直线距离1km。院子是一个曾经居住着12 户人家的典型大杂院。在过去的50~60 年间,每户人家都在院子中加建了小厨房——这些所谓的“未授权”加建形成了非常有趣的社交网络和空间属性。在以往的城市更新项目中,这些自发的加建结构都被当作城市发展残余而一概抹去。