d+a ZAO/STANDARDARCHITECTURE

01 July 2016

Many young Chinese believe that the path to greatness is equivalent to the path to riches. Beijing architect Zhang Ke feels exactly the opposite. After receiving his bachelor and master degrees from Tsinghua University, he was the first Chinese national to secure a place at Harvard University’s prestigious Graduate School of Design. After graduation, he worked for William Rawn Associates in Boston briefly before spending three years at various architectural firms in Manhattan. He quickly learned that the corporate lifestyle was not for him.

‘Practising architecture in New York allowed me to learn the reality of this world-its driving force is money, not architecture nor art,’says Zhang. ‘It made me question if I wanted to still pursue a career in architecture. A lot of people I know changed their careers after working in New York. And the people who survive become more dedicated. I made a choice; I knew that architecture does not bring a lot of money. And corporate culture in America is so strong. Individualism for architects is limited, and definitely not as interesting or diverse as the architectural culture in Europe. Most people who work in a big, famous corporation are so stable that after 30 years, they become partner—like those old guys sitting in a glass corner office. It’s a haunting image. It’s like wasting life.’

Zhang escaped by entering a competition in Beijing; it was a conservation project that preserved the last remaining bit of Ming Dynasty city wall as part of an urban park. ‘It was about how to design a park, and how to deal with the urban infrastructure relationship with rail and metro systems,’ he recalls. ‘It was about historical conservation, landscape design, architecture and urban design.’ He won the project; the park was built and he has never regretted his return to China. A series of projects followed that allowed him to build a studio with an egalitarian approach to architecture.

‘I wanted to do the opposite of the corporations,’ Zhang admits. ‘People don’t come in at a certain hour; there are no fixed hours. There is much less hierarchy. It’s more equal in terms of discussion and debate, like a university studio. At the same time, there is a degree of rigour in the drawing itself. The studio has the atmosphere of a family living together. The only serious time is when we talk about projects. We should never forget that we are architects. Most of the time we are no more than architects and our focus is architecture. But architecture is often socially related. Within the capacity of architecture, we can interact with society. To create visions for cities; to create inspiring buildings for people to live and work in, like our Novartis Campus. We were very lucky—from the beginning, we designed a primary school auditorium that provided a very strong statement of our architecture. Then we got a series of projects in Tibet. And renewal of inner Beijing on a micro scale. Gradually, we can see our work as a series, each with critical discourse carried out.’

Standard Architecture’s projects include civic buildings set in majestic rural landscapes and small bookshops in the heart of urban centres. Many are experiments in materiality, examining the social context and responding to it with architecture that is sympathetic yet challenging. Zhang’s first passion for physics and mathematics, as well as his rigorous training at Tsinghua and Harvard, comes through in his rational search for solutions. ‘We are not merely a professional studio—we are also a research office,’ he explains. ‘About 30 to 40 percent of our time is spent on researching cities. Maybe in 10 years, we will build a 1,000 metre high social housing project that can carry five villages, with people growing vegetables and raising chickens and cows in that vertical village. That would be interesting! It all comes back to science. Today, architecture has become such a service profession. We are forgetting that architecture can challenge. How do we build a city of the future utilising all the new technology, transportation and mobility devices at our disposal? How do we make a city with high energy, water and resource efficiency? How do we provide the maximum individual possibility for humans? It’s not about another skyscraper; they are already ancient.’ He grins: ‘I don’t mind being known as having a rebellious spirit.’

Although Zhang feels that young Chinese architects together are so well integrated into the global scene that there is virtually no difference between Chinese architects and their international counterparts, he does feel that China has to stop copying—and feel ashamed rather than proud of imitation. ‘That’s when we can start being really creative and inventive. I wouldn’t call it a new Chinese style. It could be a kind of sensibility that’s more subtle and can be traced back to the root, such as Ming Dynasty simplicity, elegance, refinement, mystery. There are so many things that we can be inspired by without imitating Chinese forms. It’s just like imitating western forms. They are all copies.’

‘For me, great architecture is a series of spaces that touches people sensually and intellectually—that makes people think beyond architecture.’

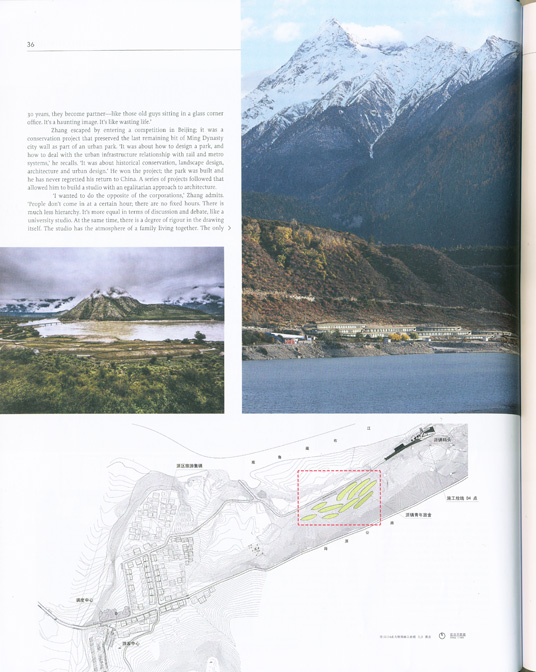

Nian g ’ou Boat Terminal

(ZAO/standardarchitecture + Embaixada)

Tibet; site area 35,000㎡/floor area 3,300㎡, 2015

‘Located in Linzhi county, Tibet, where the Niyang and Yaluzangbu rivers merge, the Niang’ou Terminal sits above a gently sloped bay, with old willows bowing over sand deltas. The bay then gradually turns into a steeper hill. Behind, layers of soft, nameless mountains. The project originates from a reading of the primal landscape: in Tibet, architecture cannot be separated from landscape. The two are equivalent. In our design we embed the building into the landscape, neither as an attachment or a detachment. Hence we arrive at this zigzagging path, which linearly integrates all complex functions. Rising from the highway, the ramp organizes parking, staff dormitories, offices, conference rooms and theatre, forming a wide platform at 3,000m altitude, guiding one’s eyes back at the magnificent union of rivers. From the highway down to 2,971m altitude, one finds a ticket office, bathrooms, waiting room, canteen and kitchen leading to a dock near the water. The ramp defines the relationship between various spaces, creating a chain of platforms and places. Each and every space firmly lodges into the landscape, subtly mediating the human body with nature. The twist and turns not only emphasizes the mountain ridges, but also calls for the spirituality of the journey. In the same way that the turn-and-descend of an Indian step complicates one’s expectation of the destination, Niang’ou Terminal also stretches the course. Every twist forms a platform, serving not only as transition between circulations, but also a pause for contemplation and a frame for lookouts. The boundaries of platforms clearly define a view frame, in which the barren hills and disheveled bushes take on a hint of humanity...a primal and redundant landscape becomes sacred when gazed and pondered upon by the human eyes. Architecture provides an angle for pondering, as well as a direction for gazing.’

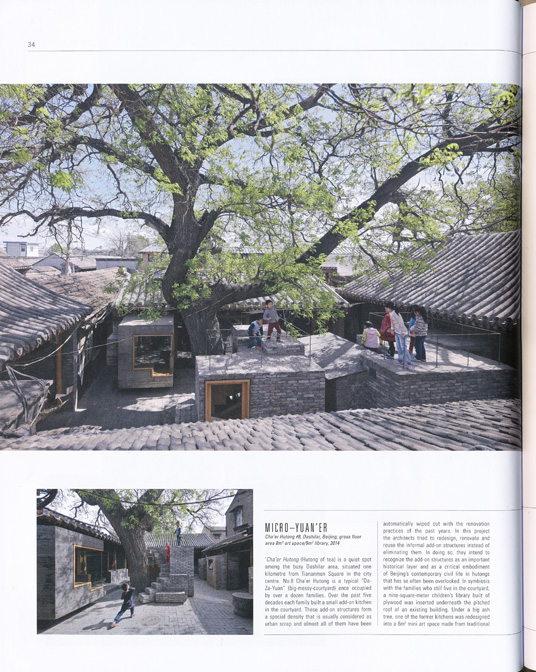

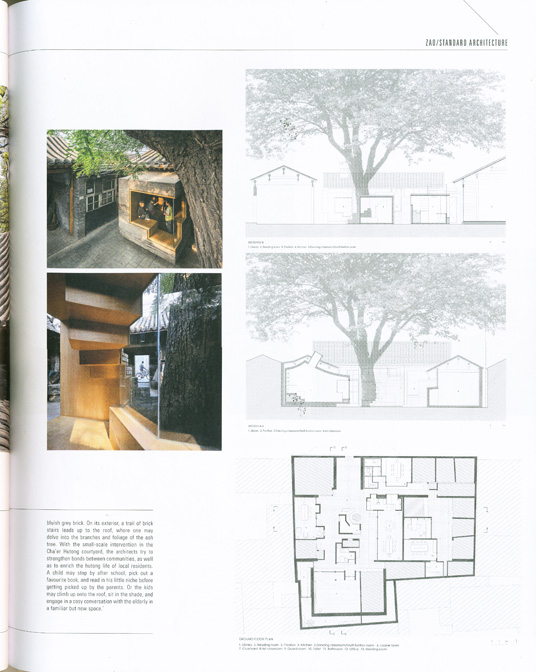

Micro–Yuan’er Cha’er

Hutong #8, Dashilar, Beijing; gross floor

area 8㎡ art space/9㎡ library, 2014

‘Cha’er Hutong (Hutong of tea) is a quiet spot among the busy Dashilar area, situated one kilometre from Tiananmen Square in the city centre. No.8 Cha’er Hutong is a typical “Da-Za-Yuan” (big-messy-courtyard) once occupied by over a dozen families. Over the past five decades each family built a small add-on kitchen in the courtyard. These add-on structures form a special density that is usually considered as urban scrap and almost all of them have been automatically wiped out with the renovation practices of the past years. In this project the architects tried to redesign, renovate and reuse the informal add-on structures instead of eliminating them. In doing so, they intend to recognize the add-on structures as an important historical layer and as a critical embodiment of Beijing’s contemporary civil life in hutongs that has so often been overlooked. In symbiosis with the families who still live in the courtyard, a nine-square-meter children’s library built of plywood was inserted underneath the pitched roof of an existing building. Under a big ash tree, one of the former kitchens was redesigned into a 6m2 mini art space made from traditional bluish grey brick. On its exterior, a trail of brick stairs leads up to the roof, where one may delve into the branches and foliage of the ash tree. With the small-scale intervention in the Cha’er Hutong courtyard, the architects try to strengthen bonds between communities, as well as to enrich the hutong life of local residents. A child may stop by after school, pick out a favourite book, and read in his little niche before getting picked up by the parents. Or the kids may climb up onto the roof, sit in the shade, and engage in a cosy conversation with the elderly in a familiar but new space.’

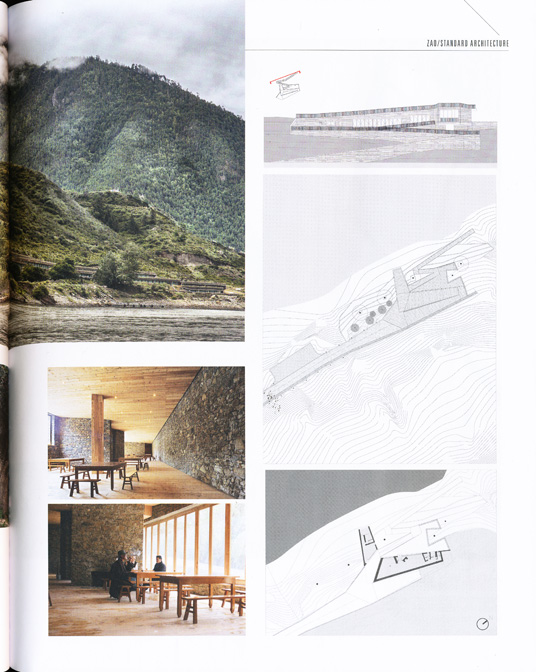

Yarlung Tsangpo Rive r Hostel

Pai Town, Tibet; site area 18,000m2/building

area 7,380㎡, 2013

‘The hostel is situated along the slope of the Yarlung Tsangpo River near Pai Town, the small locality that marks the entrance to the Grand Canyon. The site is facing the river to the north, the 7,782m high peak of Namcha Barwa to the east, the 7,294m Gyala Peri Peak to the northeast, and Mount Duoxiongla to the south. To design a hostel with one hundred rooms in such an environment posed a great challenge. Inspired by the “steps” strategy often seen in local villages when built on slopes, we decided to design a series of stepped, single-storey, linear buildings, each with unimpeded views of the river and mountains to the north and east. On four steps, each set back and grouped in a crescent-shaped form, the building is integrated like a horizontal cut in the foot of the mountain. With roofs covered by earth, shrubs and rocks, the building gently embeds itself into the sloped landscape. Viewed from a distance, the hostel disappears like a few thin leaves floating along the river.’

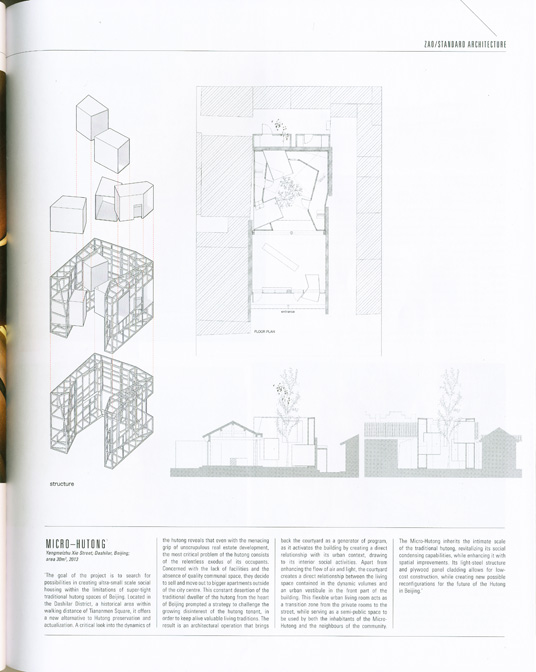

Micro–Hutong

Yangmeizhu Xie Street, Dashilar, Beijing;

area 30㎡, 2013

‘The goal of the project is to search for possibilities in creating ultra-small scale social housing within the limitations of super-tight traditional hutong spaces of Beijing. Located in the Dashilar District, a historical area within walking distance of Tiananmen Square, it offers a new alternative to Hutong preservation and actualization. A critical look into the dynamics of the hutong reveals that even with the menacing grip of unscrupulous real estate development, the most critical problem of the hutong consists of the relentless exodus of its occupants. Concerned with the lack of facilities and the absence of quality communal space, they decide to sell and move out to bigger apartments outside of the city centre. This constant desertion of the traditional dweller of the hutong from the heart of Beijing prompted a strategy to challenge the growing disinterest of the hutong tenant, in order to keep alive valuable living traditions. The result is an architectural operation that brings back the courtyard as a generator of program, as it activates the building by creating a direct relationship with its urban context, drawing to its interior social activities. Apart from enhancing the flow of air and light, the courtyard creates a direct relationship between the living space contained in the dynamic volumes and an urban vestibule in the front part of the building. This flexible urban living room acts as a transition zone from the private rooms to the street, while serving as a semi-public space to be used by both the inhabitants of the Micro- Hutong and the neighbours of the community. The Micro-Hutong inherits the intimate scale of the traditional hutong, revitalizing its social condensing capabilities, while enhancing it with spatial improvements. Its light-steel structure and plywood panel cladding allows for lowcost construction, while creating new possible reconfigurations for the future of the Hutong in Beijing.’

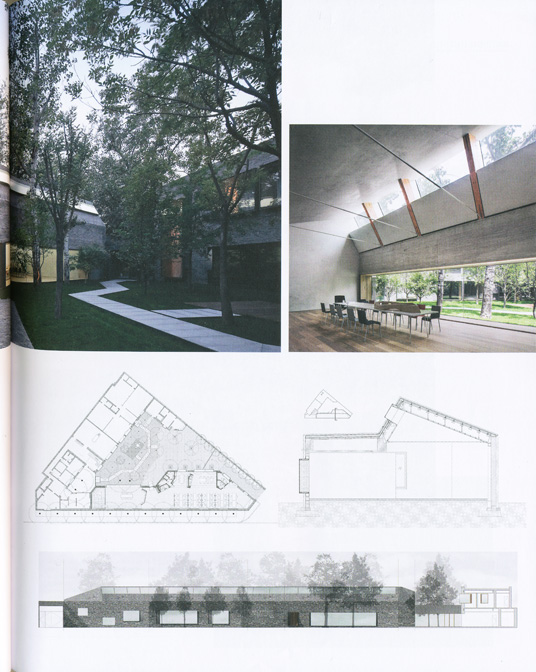

YaluntzangPu Boat Terminal

Pai Town, Linzhi, Tibet; site area 1,000m2/built

area 430㎡, 2008

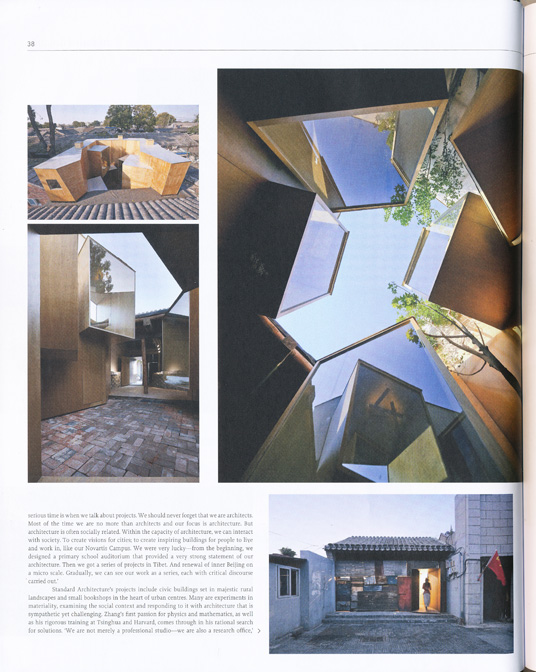

‘Carved into the landscape and hovering above the Yaluntzangpu river in Tibet, the small structure serves as a connection point between the Namchabawa snow mountain and distant valley to the local inhabitants and travellers. The steep terrain encompasses the site and guides visitors to the recessed riverfront. The ramped roof wraps around a mature poplar tree and terminates with a cantilevered wing above the water for observation and panoramic views. Contained here are a ticket office, public toilets, waiting lounge and overnight resting room to accommodate visitors sheltering from the region’s unpredictably harsh weather. The exterior walls and paths are constructed from locally sourced rocks, blending into the topography from a distance. The traditional patterns generated by the Tibetan masons retain a vernacular appearance while the windows, door frames along with the interior’s ceilings and floors are comprised of timber for a warm and inviting colour palette.’