ARCHIDEA INTERVIEW: ZHANG KE

01 April 2015

THE TRANSITION FROM RURAL LIFE TO URBAN LIFE IS A PROBLEM THAT URGENTLY NEEDS TO BE ADDRESSED

ZHANG KE

Freshness and playfulness are the qualities that first come to mind when seeing the work of Zhang’s firm Standardarchitecture. The shapes have no specific reference but often play a game with geometry. “For me, playfulness means that we allow ourselves a certain measure of intuitiveness,” says Zhang Ke, founder and director of the Beijing-based architectural office. “We try to incorporate intuition into our designs and to convey something of the same feeling to the people who will use the space and the place. Much new architecture takes itself too seriously, especially in China. It’s either too self-important, or it’s irrelevant or simply weird. Obviously I belong to a younger generation of architects. We are aware of the main issues, but we are not so naive as to pretend that we can save the world with our work. As a result we feel freer to explore the possibilities of architecture.”

- Is that what distinguishes your work from the previous generation?

“For decades there has been a discussion on how to make a new Chinese architecture, with a focus on how to make traditional Chinese architecture more contemporary. I have never taken part in that particular conversation. Contemporizing traditional forms is for me not even a point of discussion. Traditional buildings exist and you can preserve them if you want to, but mimicking them in any way results in a totally fake or even kitsch architecture. The whole discussion in China has been less about contemporariness than about a desire for icons. But there are far too many icons in China. What I am after is to discover a new kind of Chineseness. It is a Chineseness that is not obvious at first sight. It is not consciously Chinese but it should be a quality that arises naturally. So I seek a Chineseness in the sensibility, rather than in the form. It should emerge of its own accord in the design process. My approach is to go to a place – to the city wall of Beijing, to a hutong*, to the beautiful countryside of Tibet – without any idea in my mind, just to feel the place. The aim is to let ideas grow out of the place, rather than to import a certain preconceived shape or style. You could call it a kind of humility itself might be considered typically Chinese.”

- It sounds like a strategy that involves two things, the person who is experiencing the place and the place itself. Is this where your work gets personal?

”The interaction of the place with the person is exactly what makes architecture interesting. No matter what ideas, concepts or discourses go into it, the architecture always has both a local and personal dimension. But that doesn't necessarily mean having a strong personal signature. I am too young anyway to have anything like a design signature. That is something that may eventually reveal itself. When the time comes the projects may all look different but people will start to realize that they have a certain continuity. Besides, deliberately repeating a particular style would just be boring. For me the essence of architecture is to be found in the location, the spirit, the emotion and in the relationship between the architecture and its surroundings. These ingredients do not necessarily combine to form an obvious style. ”

- Your buildings have an intriguingly abstract quality. it is often not clear what they contain or what their purpose is. Is that also part of a Chinese approach or sensibility?

”Abstraction is important, and inwardness too. Abstractness matters because it derails people's reading of the building. The building doesn't immediately give away what it is about, at least not at first sight. The outward appearance does not give everything away immediately, but the nature of the building unfolds inside as a sequence of sophisticated spaces. We are interested in creating a spatial quality which is both fluid and playful. In the Novartis office building in Shanghai, for example, we have been testing the notion of an organic grid system. It develops rather like growing cells. Its geometry is akin to an organic microstructure, with cells splitting and creating space in between. One outcome of this is that we were able to dispense with corridors and we ended up with more usable space. Of course they are more difficult to design. They take more time and effort to perfect. ”

- There is also a certain ambivalence in your work: on one hand it is abstract and geometrical, while on the other it has a very concrete materiality.

”The look and tactility of the building material is crucial to me. It helps root the building in the landscape, in the region and in the urban context. It also contributes a personal, emotional touch to the building. It is like a smell that suddenly reminds you of some moment in the past, like being served a dish you haven't tasted since your childhood. The sensory qualities of a building can give rise to complex feelings. ”

- The context in which architects make their architecture has changed considerably. People travel far and wide and are scattered around the globe. What keeps them together are media like the internet and telephone. Is the rooting of your work in the context which you mentioned a way of counteracting the displacement and dispersion?

”To some extent. The physical connection to the place becomes even more important when everything is virtual. A place is something you have to experience directly. But there are two senses in which our architecture is rooted: one is the physical sense and the other is cultural. By cultural rooting I don't mean imitation, but an active connection with the context, a bond that grows and changes and evolves. I see no conflict between modernity and localism. On the contrary, their alliance opens up a huge potential for creative development. My aim is to explore the deeper significance of a place from a modern perspective. ”

- Many of your designs include courtyards and other internal open areas. Is the intention to provide space where people can meet, and perhaps where a sense of community can be restored?

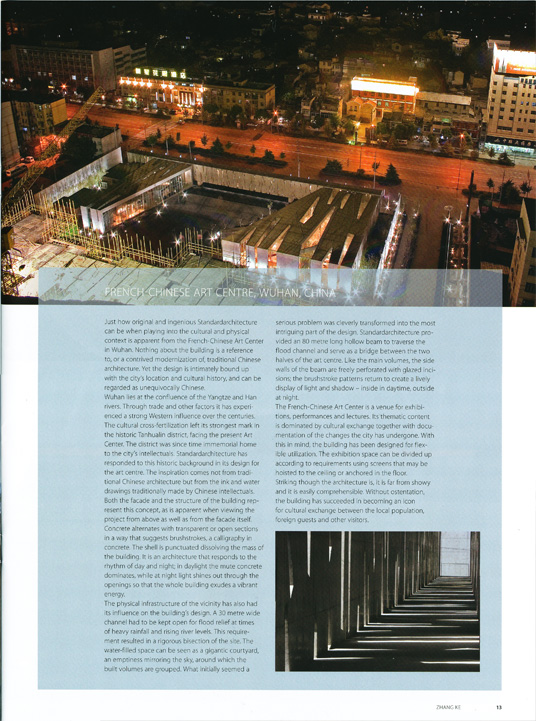

”I agree that our interest in courtyards has to do with social processes. Our hutong projects are good exam-Just how original and ingenious Standardarchitecture can be when playing into the cultural and physical Context is apparent form the French-Chinese Art Center in Wuhan. Nothing about the building is a reference to, or a contrived modernization of, traditional Chinese architecture. Yet the design is intimately bound up with the city's location and cultural history, and can be regarded as unequivocally Chinese.

Wuhan lies at the confluence of the Yangtze and Han rivers. Through trade and other factors it has experienced a strong Western influence over the centuries. The cultural cross-fertilization left its strongest mark in the historic Tanhualin district, facing the present Art Center. The district was since time immemorial home to the city's intellectuals. Standardarchitecture has responded to this historic background in its design for the art center. The inspiration Comes not from traditional Chinese architecture but from the ink and water drawings traditionally made by Chinese intellectuals. Both the facade and the structure of the building represent this concept, as is apparent when viewing the project from above as well as from the facade itself. Concrete alternates with transparent or open sections in a way that suggests brushstrokes, a calligraphy in concrete. The shell is punctuated dissolving the mass of the building. It is an architecture that responds to the rhythm of day and night; in daylight the mute concrete dominates, while at night light shines out through the openings so that the whole building exudes a vibrant energy.

The physical infrastructure of the vicinity has also had its influence on the building's design. A 30 metre wide channel had to be kept open for flood relief at times of heavy rainfall and rising river levels. This requirement resulted in a rigorous bisection of the site. The water-filled space can be seen as a gigantic courtyard, an emptiness mirroring the sky, around which the built volumes are grouped. What initially seemed a serious problem was cleverly transformed into the most intriguing part of the design. Standardarchitecture provided an 80 metre long hollow beam to traverse the flood channel and serve as a bridge between the two halves of the art center. Like the main volumes, the side walls of the beam are freely Perforated with glazed incisions; the brushstroke patterns return to create a lively display of light and shadow-inside in daytime, outside at night.

The French-Chinese Art Center is a venue for exhibitions, performances and lectures. Its thematic content is dominated by cultural exchange together with documentation of the changes the city has undergone. With this in mind, the building has been designed for flexible utilization. The exhibition space can be divided up according to requirements using screens that may be hoisted to the ceiling or anchored in the floor.

Striking though the architecture is, it is far from showy and it is easily comprehensible. Without ostentation, the building has succeeded in becoming an icon for cultural exchange between the local population, foreign guests and other visitors. ples of what we are trying to achieve. The cities of China are undergoing rapid change, probably even faster than the cities of Europe after the Second World War. We don't imagine we can save the world with our architecture, but even our small projects can raise questions and suggest what might be possible. We have often been criticized at first but in the end we get a lot of positive reactions from the neighbourhood. ”

- The hutong is widely said to be a phenomenon on the verge of extinction. The few that remain are preserved as historic relics. So what is the relevance of your two self-initiated hutong projects here in Beijing?

”I don't think the hutong is necessarily a thing of the past. In both our projects the intention was to prove that there are ways to be true to our times as well as to the spirit of the hutong. One project showed us that a house without a courtyard could be transformed into one with courtyard, and could then theoretically house two families. It is satisfying that the courtyard now functions as a public space where neighbors hold exhibitions and watch movies together.

Our other hutong project tells us that all the unregistered extensions built in the hutongs over the last thirty or forty years form part of an interesting history. Each courtyard used to belong to one family. Under communism that became eight families, and each household needed its own small kitchen. The result was a high population density in the hutongs. I am certain that ninety-nine percent of the additions will eventually be removed, although we are not convinced that it is necessary. Our intention is to pose the question whether the additions could be seen as a positive development. We aim to preserve the more recent historical layer, while renovating or remodelling the hutongs to support a programme beneficial to the vitality of the neighborhood-for example, an art school, a children's library, a small exhibition space, a café or a multifunctional studio space for dancing and so on. ”

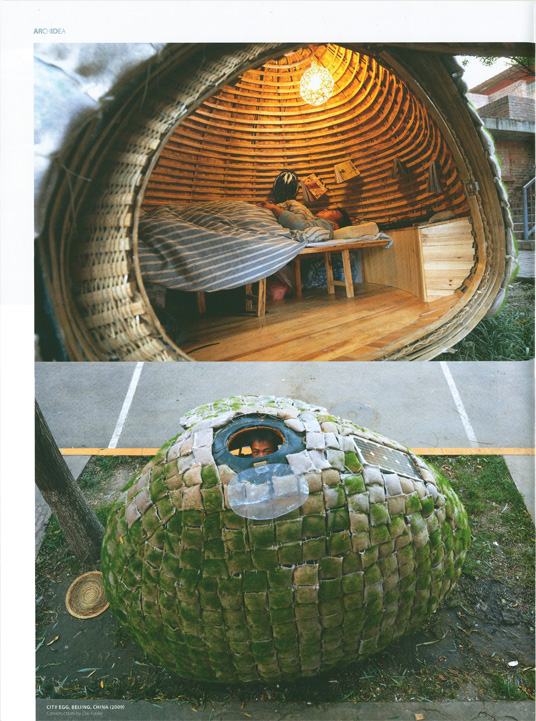

- You have also been responsible for some visionary projects. You proposed turning the highways of Beijing into conveyor belts for cars and you designed sky-high 'Village Mountains' to house migrants from the countryside. Then there are those living-pods for migrant workers, the 'Eggs of the City'. Do these works of imagination matter as much to you as the hutong projects?

”They are definitely equally important. They differ in scale but they all address the urbanization process and the living conditions of people migrating to the city. The projects all address real problems like population density, the traffic congestion that afflicts most Chinese cities and the increasingly acute land shortage. On one hand, there are our small scale projects which can be seen as proposals for new ways to use space in an urban context. They illustrate the possibility of restoring and revitalizing a community. On the other hand, there are our visionary designs which react in a more direct way to the large-scale problems of rapid urbanization. For three decades Chinese cities have been expanding without the benefit of a vision. A chronic shortage of building land has developed and now we are worryingly eating into our supply of farmland. For all those years nobody paid serious attention to those problems. The transition from rural life to urban life has created a situation that needs urgent attention. ”

- Do you intend to continue making these visionary designs now you are realizing more and more built projects?

“Certainly. We are not interested in making buildings and nothing else. At last people in China are sensing the urgency of looking beyond our day-to-day needs and thinking about what is happening to our cities. It seems to have reached a critical pitch. Now that the economy is slowing down, people are beginning to reflect on what happened over the recent decades. They are asking themselves what should be happening to make the city more enjoyable and livable in the long term.”

- Do you think that can still be achieved? Or is it already too late?

“For a city like Beijing, I am not that pessimistic. Beijing is a future-minded city, so it makes sense to lead it strategically in a better direction. The old city has already been practically destroyed with only a few small patches of the historic city left over. And that is by pure chance. Now we need to think as well as build. That's what makes the architect's profession so exciting, especially in these times in China.”